How saber-toothed cats’ baby teeth kept their adult fangs from breaking

The saber-toothed cats that once prowled modern day California had more distinct dental features than even their sabers would suggest. Some of the complete skulls had a tooth socket occupied by two teeth–a permanent saber tooth and a baby tooth that would eventually fall out. These double-toothed sockets may have helped stabilize their signature front fangs and keep them from breaking off. The findings are described in a study published April 8 in the journal The Anatomical Record.

Sharp, but easily lost teeth

The study looked at saber-toothed cat fossils found in the La Brea Tar Pits in Los Angeles. There are at least five separate lineages of saber-toothed animals that have evolved around the world. The species Smilodon fatalis roamed widely across North America and into Central America, before going extinct about 10,000 years ago.

Paleontologists studying these fossils have been stumped by why the adult animals with two canines that are more like thin-bladed knives avoided breaking them. During periods of food scarcity, saber-toothed cats broke their teeth more often than they did during times of plenty, potentially due to altered feeding strategies and eating rocks. Paleontologists also still do not know how saber-toothed animals hunted prey without completely breaking these unwieldy teeth.

In an earlier study, a team from the University of California, Berkeley speculated that a baby tooth helped stabilize the permanent tooth against sideways breakage as it emerged from the gums. The baby tooth–also called a milk canine–are the types of teeth that all mammals grow and lose sometime before adulthood. The growth data seemed to imply that the two teeth sat there together for up to 30 months into the animal’s adolescence.

[Related: Mighty sabertooth tigers may have purred like kittens.]

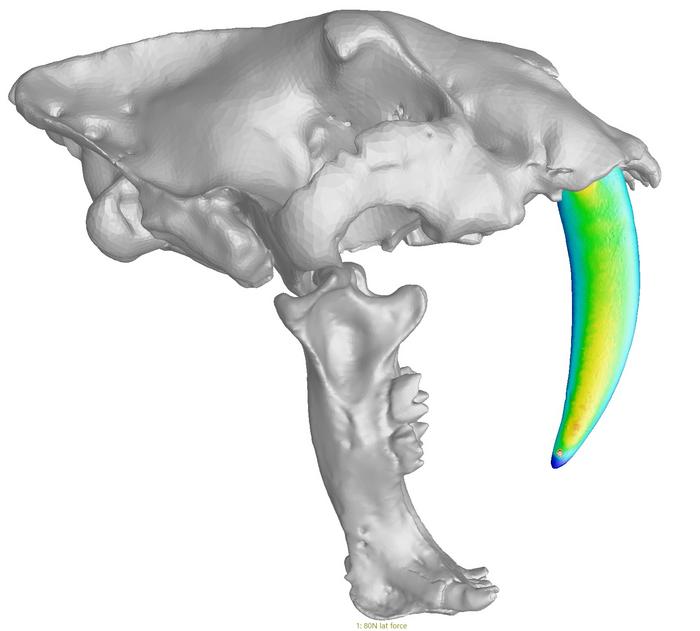

To investigate this tooth stabilization theory for the new study, the team used computer models that simulate a saber-tooth’s strength and stiffness against the sideways bending that happens when the saber tooth grows outwards. They also tested and bent plastic models of saber teeth. They found evidence that while fearsome, the saber tooth would have been increasingly vulnerable to breaking off as they emerged from the gums. Having the baby or milk tooth behind it would have worked like a buttress to make it significantly more stable.

The temporary baby milk canine remaining behind long after the permanent saber tooth erupted indicates that it would have stayed in until the maturing cats learned how to hunt without damaging them.

“The double-fang stage is probably worth a rethinking now that I’ve shown there’s this potential insurance policy, this larger range of protection,” study co-author and Cal Berkley paleontologist Jack Tseng said in a statement. “It allows the equivalent of our teenagers to experiment, to take risks, essentially to learn how to be a full-grown, fully fledged predator. I think that this refines, though it doesn’t solve, thinking about the growth of saber tooth use and hunting through a mechanical lens.”

Applying some beam theory

Some of the double-fanged specimens found from the La Brea tar pits are considered rare cases of animals with a delayed loss of a baby tooth. This gave Tseng the idea that maybe they had an evolutionary purpose. He used the beam theory engineering analysis to model real saber teeth.

“According to beam theory, when you bend a blade-like structure laterally sideways in the direction of their narrower dimension, they are quite a lot weaker compared to the main direction of strength,” said Tseng. “Prior interpretations of how saber tooths may have hunted use this as a constraint. No matter how they use their teeth, they could not have bent them a lot in a lateral direction.”

The beam theory combined with computer models that simulated the sideways forces of a saber tooth could withstand before breaking. As the tooth got longer, it became easier to bend, increasing the chance of breakage.

[Related: This tiger-sized, saber-toothed, rhino-skinned predator thrived before the ‘Great Dying.’]

When a supportive baby tooth was added to the beam theory model, the stiffness of the permanent saber kept pace with the bending strength. This baby tooth essentially reduced its chance of breakage.

The study has implications for how saber-toothed cats and other saber-toothed animals like Africa’s Inostrancevia africana may have hunted as adults. They likely used their predatory skills and strong muscles to compensate for the more vulnerable canines.