Europe’s oldest human-made megastructure may be at the bottom of the Baltic Sea

A stone wall underneath the Baltic Sea may be the oldest known megastructure built by humans in Europe. It dates back about 11,000 years to the Stone Age, and was first discovered in 2021 about six miles off of Germany’s Baltic coast. The findings are described in a study published February 12 in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).

[Related: Neanderthals and modern humans intermingled in Europe 45,000 years ago.]

The Blinkerwall is about half a mile long along the Bay of Mecklenburg. It was initially spotted by accident when a team of scientists from Kiel University in Germany were using a multibeam sonar system from a research vessel to study the crust of the seafloor.

The team believes that Stone Age hunter-gatherers likely built it about 11,000 years ago to hunt reindeer. Hunting walls like this would catch herds of animals that are more likely to run parallel alongside obstacles instead of jumping over them.

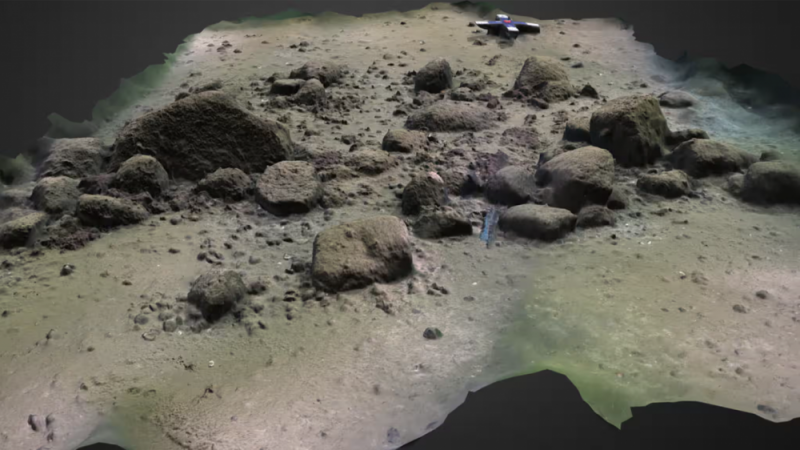

The roughly 1,500 stones connected to nearly 300 bigger boulders that make up the Blinkerwall are aligned so regularly that the possibility that the arrangement of stones formed naturally along the seafloor seems unlikely.

Scientists from the Leibniz Institute for Baltic Sea Research Warnemünde (IOW), Kiel University, the Centre for Baltic and Scandinavian Archaeology, the German Aerospace Center, the Alfred Wegener Institute, Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research and created a detailed 3D model of the wall. They also used modern geophysical models to reconstruct what the landscape would have looked like thousands of years ago. Sediment samples from the basin just to the south of the wall helps them narrow down the possible time period when the wall was built. It is the first known discovery of a Stone Age hunting structure in the Baltic Sea region.

“Our investigations indicate that a natural origin of the underwater stone wall as well as a construction in modern times, for instance, in connection with submarine cable laying or stone harvesting are not very likely. The methodical arrangement of the many small stones that connect the large, non-moveable boulders speaks against this,” study co-author and IOW geophysicist Jacob Geersen said in a statement.

Located just on the southwestern flank of a ridge on the seafloor, the wall stands where a former lake or bog would have been. While the Baltic Sea is currently about 68 feet deep in this location, the Blinkerwall was likely built before the sea level rose about 8,500 years ago, towards the end of the last Ice Age. Huge swaths of this previously accessible landscape were buried under the melting glacier water that formed the Baltic.

Excluding the unlikely possibility that a natural process built the wall or a modern origin, it only could have been built when the landscape was still not flooded by the Baltic Sea.

“At this time, the entire population across northern Europe was likely below 5,000 people. One of their main food sources were herds of reindeer, which migrated seasonally through the sparsely vegetated post-glacial landscape,” study co-author and University of Rostock archaeologist Marcel Bradtmöller said in a statement. “The wall was probably used to guide the reindeer into a bottleneck between the adjacent lakeshore and the wall, or even into the lake, where the Stone Age hunters could kill them more easily with their weapons.”

[Related: Blueprints engraved in stone from Saudi Arabia and Jordan could be the world’s oldest.]

A 2014 study described a 9,000 year-old structure at the bottom of Lake Huron in Michigan that was likely for hunting Caribou. Low-walled hunting structures called desert kites have also been discovered in parts of the Middle East and Africa.

The last reindeer herds disappeared from what is now the Baltic Sea 11,000 years ago, as the climate warmed and forests spread. The team believes that it was unlikely that the wall was built after reindeer left the area and would make it the oldest human structure found in the Baltic.

Future investigations into the area are planned, with side-scan sonar, sediment echo sounder, and multibeam echo sounder devices. Using luminescence dating to determine when it last was exposed to sunlight may also help hone in on a more accurate date of construction. The team also plans to reconstruct the ancient surrounding landscape in greater detail.