Blasting coffee grounds with ultrasonic waves creates a 60-second cold brew

As the weather continues to warm, many coffee drinkers currently are making their annual transition over to iced coffee. But for those with more sensitive stomachs, cold brew’s comparatively low acidity makes it their preferred year-round caffeine fix. This smoother, creamier, and sweeter brew comes from allowing grounds to steep in refrigerated water for upwards of 24 hours. Unlike hot brewing, the additional time and cooler temperatures draw out less acids while allowing the coffee’s remaining chemicals time to muddle.

Iced or cold brew, demand for the chilled drinks are on the rise at coffee shops. This, however, can create logistical problems, since cold brewing usually requires 24 hours refrigeration time to produce properly flavor-rich, less-bitter concentrate shots.

Not willing to wait around any longer, a group of researchers at Australia’s University of New South Wales recently experimented with an intense alternative brew strategy: blasting coffee grounds with ultrasonic waves. The result, says chemical engineering professor Francisco Trujillo, is now his “favorite way to drink coffee.” News of Trujillo’s preferred cold brew concentration arrived during a recent chat with New Scientist, alongside a new rundown of his team’s work in the journal, Ultrasonics Sonochemistry.

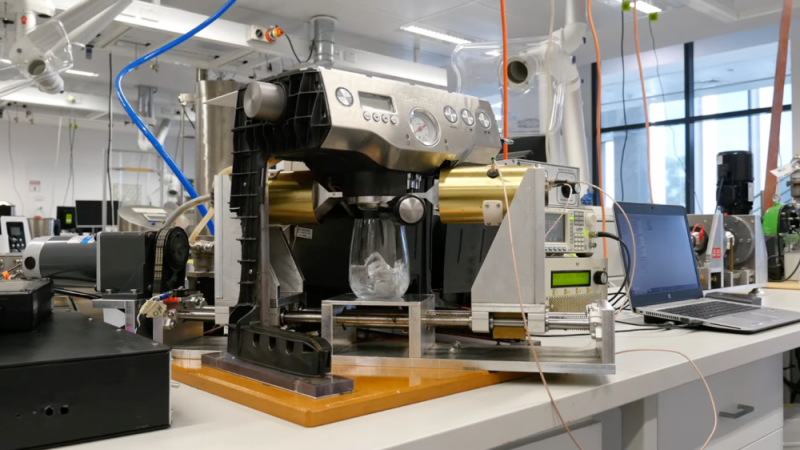

The researchers actually discovered the new time-saving approach while working on a separate soundwave experiment. Trujillo and colleagues initially wondered if further breaking up coffee grounds through what’s known as acoustic cavitation might yield higher antioxidant levels. To test it out, the group attached a Langevin transducer to a Breville Dual Boiler BES920 espresso machine and set it to blast their coffee with 38.8 kHz frequency sound waves. While the resultant antioxidant count remained largely the same, the group still noticed the final cup of coffee was impressively tasty.

Further trial and error honed their cold brew shots. One setup exposed the espresso to 60 seconds of ultrasound waves while pumping ambient temperature water through the grounds at 12-second intervals. In another array, they also lengthened the total time to 3 minutes. Both approaches were then followed by taste tests at the Queensland Alliance for Agriculture and Food Innovation to assess the coffee’s texture, flavor, aroma, and aftertaste.

The final verdicts? The 1-minute brew offered largely similar scores as the traditional 24-hour method, although it does appear to rank lower when it comes to aroma intensity—implying under-extraction. And while that aroma intensity returned with the 3-minute brew, it also made it a little more bitter. Essentially, it seems that somewhere between 1-3 minutes of ultrasonic acoustic cavitation can produce arguably the same quality cold brew, without all that waiting.

Of course, what scientists saved in time was offset by costs, at least initially. According to New Scientist, the first espresso machine-transducer setup required nearly $10,000 of equipment. That said, Trujillo did note further refinement reduced the financial burden to “a fraction of the cost.” But even if the ultrasonic method never makes it out the lab, at least Trujillo’s team will remain properly caffeinated to continue any future advancements in coffee tech.