I lift heavy weights to soothe my fibromyalgia pain—here’s what the science says

I THINK THE BARBELL SAVED ME. Before that, I was toiling under the bar as a sports-bra-clad 20-something, lifting heavy things off the floor in pursuit of vain aesthetic goals. Then one day, that version of my life evaporated over a small bowl of rolled oats.

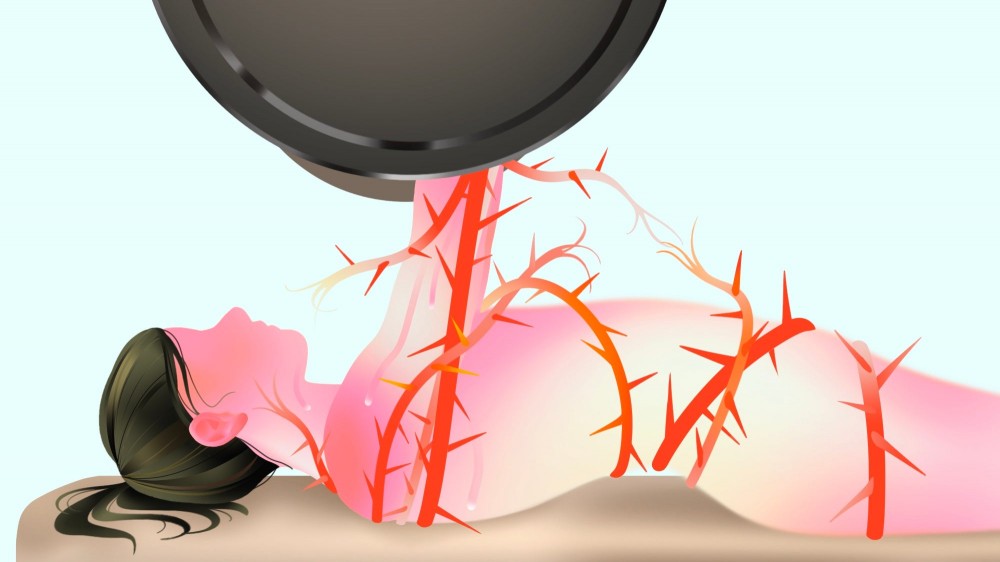

That pivotal morning, I felt something novel: earth-shattering pain like I’d never felt before. It crept up and down my back, hammering my vertebrae as if they were piano keys. Over the next few weeks, this percussive melody swelled to a full-body symphony. Agony spread to my limbs and tightened, viselike, around my ribs until I suspected I was having a heart attack. My sleep shattered into tiny, torturous fragments. I was suddenly sensitive to bright lights and loud noises, wading through waves of nausea, and sinking headlong into brain fog.

For a few months, securing a diagnosis became my sole mission. I ignored work to Google symptoms and spent my savings on medical appointments. I ran the gamut: cardiologist to pain specialist, general practitioner to gynecologist—a new diagnostician for each mysterious symptom. No one offered me an answer.

With the battery of tests exhausted, a kind doctor in a Kolkata clinic finally diagnosed me with a condition traditionally defined by exclusion: fibromyalgia syndrome (FMS). But there was no pill to take, no detailed road map to follow for the rest of my lifelong journey.

I had no idea that I would come to view my longtime acquaintance—that 45-pound stainless-steel bar and its set of stackable plates—in a completely different light, and that it would help me chart my path.

What makes FMS so hard to diagnose?

Most people with fibromyalgia have had somewhat similar diagnostic experiences. The helpless trudging from specialist to specialist. The constant, confusing pain. The sense of isolation. No one ladled the biryani for me, stirring the individual symptoms into a cohesive diagnosis like cardamom pods, fried onions, and chunks of mutton coalescing atop layers of rice. To be fair, it’s not exactly their fault. The US National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases describes FMS as a chronic disorder that causes pain and tenderness throughout the body, fatigue, sleep problems, and heightened sensitivity to pain. But what’s really important to absorb is the institute’s caveat that “scientists do not fully understand what causes it.”

At least some of this uncertainty can be attributed to medicine’s struggle to conceptualize FMS, let alone find a suitable test for it. While key fibromyalgia-like symptoms were identified in the early 1820s, the term wasn’t officially coined until 1976. It took another decade for the American Medical Association to recognize FMS as an official diagnosis. There may be some gender bias involved too: The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports that women are twice as likely to have FMS as men (though the extent it’s underdiagnosed in men is an active area of research). This is sobering, considering that medicine has historically ignored women’s pain—making them wait longer in emergency rooms, dubbing them “emotional,” and nudging them to just ignore the “little pain, honey.” Even in 2019, I found myself going through the rigmarole of not inconveniencing others, not sounding “too hysterical”—because if it doesn’t show up on medical imaging or in a blood panel, it isn’t real.

With FMS, the diagnosis is hard won, but what follows is harder. You may navigate, alone, the cesspool of a vague and nebulous condition with little medical support, using generalized prescriptions from practitioners. You may get shunted from osteology to neuroscience, rheumatology to pain management. You might find your way to the fibromyalgia subreddit, where fellow chronic pain sufferers can validate your story. What helped me most was forming some semblance of a community. I began to figure out how to move forward.

The relationship between FMS and resistance training

Few blows were harder and more bewildering than being advised by the many specialists I saw to give up weight training. My life was going to be hard with fibromyalgia, they reckoned—wouldn’t I rather try light tai chi or restorative yoga instead? Already frustrated (“chronic pain” meant I’d never be cured, and that was crushing), I found this a bitter pill to swallow. I’d been lifting weights since I was 18, and all those deadlifts, bench presses, and heavy barbell squats had given me a dopamine release that few other things had. Not even India’s inequitable COVID-19 pandemic could keep me away—I had settled into a makeshift home gym, pertinaciously jotting down the day’s reps and sets in a mass of squiggles on my phone. These numbers spoke to me in their own love language, soothing my anxiety. Often, they were the fulcrum that balanced an entire day.

Again, I cannot entirely blame my doctors. Their recommendation stemmed from a lack of new research. Guilherme Torres Vilarino, who has a doctorate in human movement science and works as an assistant professor at Santa Catarina State University in Brazil, explains that studies on resistance training and FMS are still too recent and limited for medical practitioners to incorporate them into treatment plans. One of the earliest studies that investigated the effects of resistance training in patients with FMS—wherein a group of premenopausal women with FMS took part in 21 weeks of progressive strength training—was published in 2021, but resistance training’s effects on people with FMS remained a rare research topic until a few years ago. “Scientific information does not reach the professionals who are working on a daily basis so quickly, so there’s a certain outdatedness,” Vilarino says. “Many professionals still think that exercise with loads will make pain worse.”

This school of thought isn’t unfounded. The Journal of Clinical Investigation points out that people with FMS have such debilitating pain because their sensory neurons “have heightened sensitivity to touch and pressure, as if their neurons are primed or supercharged to transmit pain signals in response to even minimal changes in the environment.” Everyone with FMS has their own triggers, and I’ve been able to zero in on mine over the years. My most common is a night of poor sleep, which invariably elicits shooting pain in the mornings.

The Lancet takes this further to suggest that people with fibromyalgia experience “nociplastic pain,” a relatively newly defined type of pain that’s different from nociceptive pain (caused by inflammation or tissue damage) and neuropathic pain (caused by nerve damage). The Lancet acknowledges that there’s more to learn about nociplastic pain, but that one factor could be altered pain modulation—the process by which the body handles pain signals. The medical journal also says that this kind of pain can be “more widespread or intense, or both, than would be expected given the amount of identifiable tissue or nerve damage.”

It makes sense, then, that many with FMS instinctively recoil from anything that feels out of place and could trigger symptoms. Perhaps resistance training is a fan to the flame for many diagnosed with fibromyalgia. But research now suggests that for some fibromyalgia patients, at least, weights are worth a closer look.

Why resistance training may be able to help with fibromyalgia

Since FMS research really began taking off in the past couple of decades, studies have sought to find out what the syndrome actually does to you and how exercise factors in. A 2006 study in Physical Therapy, for example, compared the functional physical performance and strength of women with fibromyalgia, women of similar weights and ages without FMS, and healthy older women. The results were alarming: The young women with FMS and the healthy older women had similar lower-body strength and functionality, which suggests fibromyalgia could increase the risk of premature age-related disability.

This is concerning for women with FMS, especially those who may avoid physical activity for fear of triggering pain—because they may lose skeletal muscle mass while recovering. Science has established that if you don’t use it, you lose it. The Scandinavian Journal of Medicine and Science in Sports, for example, found that you can lose significant muscle after only 10 days of “detraining” (i.e., after returning to pre-study levels of activity with no resistance or endurance training), while The American Journal of Sports Medicine found that even rugby and football players began to lose both upper- and lower-body strength after just three weeks of detraining. Athletes and fitness junkies aside, COVID demonstrated that sarcopenia (loss of skeletal muscle mass) is an unavoidable consequence of lying in bed.

In that context, it’s helpful to look at what resistance training (RET) does to fibromyalgic pain. High-quality studies have linked muscular fitness to lower all-cause mortality over the years in healthy individuals, and the American College of Rheumatology says exercise is the most effective treatment for FMS, but it does not single out RET. Still, recent research has focused specifically on how training for that muscular fitness could affect pain in FMS sufferers. A 2015 study of 130 women with FMS symptoms spanning up to 35 years found that RET led to significant improvement for current pain intensity, pain disability, and pain acceptance. The researchers did, however, stress that each participant needed to be actively involved in planning her own workout, a practice they said would help the women manage their progression around their own health problems.

In 2022, three Chinese researchers analyzed a number of studies across several databases (including PubMed and the China National Knowledge Internet) and found that a combination of resistance and aerobic training might be the best way to alleviate pain among FMS patients. There’s also a 2013 examination of literature across databases (from the World Health Organization to the Cochrane Library) that suggests moderate-intensity RET reduces tender point sensitivity and pain in people with FMS, but also acknowledges that the evidence is low-quality—a technical term indicating that more studies are required. Then there are the mixed results, like those of a 2022 study of 41 women with FMS. This study found after 24 weeks of gradual and progressive strength training, the participants had reduced pain and improved sleep quality…but not reduced anxiety and fatigue, two other key FMS symptoms.

If you take one thing away from all this, it should be that while RET has been shown, in small, sporadic studies, to support pain reduction, we still lack studies that deeply probe whether patients outside a controlled trial can transfer those habits to their daily lives. The key, then? Start slow, and build slowly.

After one 12-week strength-training program—in which participants did 11 exercises twice a week, doing each exercise for a set of eight to 12 repetitions at 40 to 60 percent of their one-rep max and eventually progressing to 60 to 80 percent of their one-rep max—women with FMS saw improved strength and daily functionality; however, tender point sensitivity stayed the same.

Another study published in Arthritis Research and Therapy had women with FMS begin lifting weights that were 40 percent of their one-rep max for a training period of 15 weeks, and that aforementioned 2001 study published in Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases started women with FMS at exercise loads of 40 to 60 percent of their one-rep max for a 21-week program. The results of both studies were promising: The former found significant improvements in current pain intensity, and at a post-trial examination, the latter found significant improvement in neck pain, fatigue, and depression.

Lynn B. Panton, a lead author on the study involving a 12-week strength-training program, suggests cautious progression. Panton, who has a doctorate in exercise physiology and is a professor of exercise science at Florida State University, suggests a multimodal program (one that combines RET, aerobic training, yoga, mental health therapy, and other activities). But even with such variety to choose from, she cautions against overwork. “One of the things we did in our studies was not to allow women, when they felt well, to do too much—because then they would usually overdo it,” Panton says.

Annette Larsson, a physiotherapist with the University of Gothenburg, points out another obstacle to incorporating RET into a multimodal program for FMS patients: “Proximity to training facilities and the cost of gym membership are important factors in whether a person with FMS chooses RET or not.” Plus, there are many, she says, who might believe they have insufficient knowledge of the exercises and don’t want to risk hurting themselves. Given the importance some researchers have placed on FMS patients being actively involved in their own workout planning, a lack of familiarity and confidence is certainly a challenge, but research has already laid the groundwork.

“You should choose to start with low weights and increase the load at a slow pace so you can get used to it. but then don’t be afraid to try to train on heavier loads with few repetitions.”

—Annette Larsson, Physiotherapist

How often you lift, and how much, varies from person to person, but studies have suggested a gradual-loading approach can have both physical and mental benefits. “In the beginning, we start light, 50 to 60 percent [of a one-rep max], two sets, eight to 12 reps. We find it tolerable, manageable, with easy progression,” says J. Derek Kingsley, an associate professor of health sciences at Kent State University and a certified exercise physiologist who has led several studies on resistance training for women with FMS and chronic disease. “It shows the women they are capable, for one, and allows for time to learn the lifting techniques (breathing, for instance).”

When I was figuring out my own resistance load, months after my diagnosis, I stopped to listen to my body, and to the sage words of weightlifters such as Megan Densmore, who’s had FMS since she was 14. Densmore has said that it took her five years to rebuild her strength and endurance, during which time she would often get a “flare” (an array of FMS symptoms, caused by a trigger) if she did too much. What could “too much” be, then? The Arthritis Foundation has suggested gradually scaling up to just a few exercises per week, but at heavier loads for fewer reps.

This appears to be important, as tempting as it may be to train with lighter loads that you can lift for many, many reps. A 2013 study examined 10 recreational athletes across three different rep ranges (high, low, and medium) and found that the high-rep athletes had the most lactate accumulation in their bodies after they finished their exercises. That’s important because a 2021 study in the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health found that 10 women with FMS generally viewed heavy-load exercise sessions more positively than light- to moderate-load ones, and Larsson says excess lactic acid accumulation after many light reps could be a reason why. “In [that] study, it was shown that women with fibromyalgia actually preferred to train with heavier weights and fewer repetitions.” Vilarino, however, cautions that few studies specifically compare the effects of high-intensity training with those of low-intensity training for FMS patients. He still recommends starting with lighter loads, only increasing if one feels confident. “This progression should only be made if the patient does not imagine that this could worsen the symptoms.”

My routine, post-diagnosis

There are recommendations galore for incorporating RET into one’s training module, along with aerobic exercise, yoga, tai chi, and more. Aerobic exercise, especially, Kingsley says, can increase heart rate variability, thereby reducing your risk of cardiovascular disease, while Larsson suggests that the most important thing is to find a form of training you enjoy and that works with your life. “Get moving, that’s the key,” Kingsley says.

And there are plenty of ways to move, no matter what your body is capable of. I, for one, have simply found my way back to an old favorite. I’ve settled into resistance training three days a week, supplemented by a day or two of yoga or high-intensity interval training (HIIT). I think of how I’ve naturally gravitated, led by an FMS-fueled brain, toward deadlifting, benching, and squatting, hauling heavy but rarely for too long, always listening, tuned into the sounds of my body. I think, also, of the personal records I continue to track in a set of squiggly lines within an endless phone note, assured that my FMS flares will now be fewer and farther between than they were in 2019 when all this started.

When I asked Larsson about the efficacy of my own training module, she suggested I was on the right track and advised a similar approach: “You should choose to start with low weights and increase the load at a slow pace so you can get used to it. But then don’t be afraid to try to train on heavier loads with few repetitions.”

Beyond physical benefits, there is my mind, soothed, and the self-love welling up when I feel a weight lift off the ground. That self-esteem bump, Panton says, is indeed a prime reason to do all this. The effects of FMS on depression and anxiety, and vice versa, are well documented, with evidence of higher numbers of psychiatric conditions, including post-traumatic stress disorder, in people with FMS compared to the general population. Using exercise to counter that, even for a short while, can be heartening. “Studies show that RET can help with PTSD, empowering women and improving self-efficacy and self-esteem. All women can get the benefits,” Panton says. Kingsley says the same, although he concedes that I am still part of a “tiny minority”—women who have fibromyalgia and actively veer toward resistance training. If the studies keep coming, and stigma falls away to reveal a deeper understanding of FMS, this minority could grow.

Why, then, does the idea of RET as inherently damaging still permeate popular discourse? My earliest slew of doctors, for example, were not FMS experts and shrank from the idea of me returning to strength training. Panton and Kingsley say it’s likely about perception. RET, Kingsley says, is viewed as higher intensity than many other exercises, but it doesn’t have to be. In fact, just 30 to 60 minutes of muscle-strengthening activities like RET per week is enough to reduce the risk of premature death. Consider starting with a couple of 15-minute sessions a week.

Panton also acknowledges that using a weight room can be seriously intimidating, especially for someone who hasn’t ever set foot in one. That said, once you’re in there, you may see improvements quite quickly, especially if you have the guidance of a kind soul or two with knowledge of your pain—a doctor, a partner, or a specialized trainer.

It’s been four years since my diagnosis, and since then, I’ve moved through tidal waves of emotion—first mourning for a body that once was, then feeling rage, grief, and quietude all at once. The struggle, as the kids say, is real: A bad pain flare will push me, frustrated, away from the squat rack for a day or two, and a bout of nausea can physically stop me from lifting a weight for half a week. In all of this, at least, I’ve earned a more heightened awareness of my body—a silver lining that gives me comfort when I’m low. Science will agree that movement looks different on different days, and research can’t yet confirm exactly what movement means for those of us with FMS. But I’ve come to understand that sometimes standing still, inert, hyperaware in the tsunami that is chronic pain, is movement itself.

Life after an FMS diagnosis isn’t exactly the same, they tell you. But who says it has to be worse?

Read more PopSci+ stories.