Podcast: Artificial Intelligence – Global Governance, National Policy, and Public Trust with Allan Dafoe and Jessica Cussins

Experts predict that artificial intelligence could become the most transformative innovation in history, eclipsing both the development of agriculture and the industrial revolution. And the technology is developing far faster than the average bureaucracy can keep up with. How can local, national, and international governments prepare for such dramatic changes and help steer AI research and use in a more beneficial direction?

On this month’s podcast, Ariel spoke with Allan Dafoe and Jessica Cussins about how different countries are addressing the risks and benefits of AI, and why AI is such a unique and challenging technology to effectively govern. Allan is the Director of the Governance of AI Program at the Future of Humanity Institute, and his research focuses on the international politics of transformative artificial intelligence. Jessica is an AI Policy Specialist with the Future of Life Institute, and she’s also a Research Fellow with the UC Berkeley Center for Long-term Cybersecurity, where she conducts research on the security and strategy implications of AI and digital governance.

Topics discussed in this episode include:

- Three lenses through which to view AI’s transformative power

- Emerging international and national AI governance strategies

- The risks and benefits of regulating artificial intelligence

- The importance of public trust in AI systems

- The dangers of an AI race

- How AI will change the nature of wealth and power

Papers and books discussed in this episode include:

- The Future of Life Institute’s Global AI Policy Resource

- Allan’s new paper titled, AI Governance: A Research Agenda

- United States’ 2019 National Defense Authorization Act

- French national AI strategy: AI for Humanity

- French President Macron’s Interview with Wired on AI

- Google’s AI Ethics principles

- Charlevoix Common Vision for the Future of AI

- Superintelligence by Nick Bostrom

- Chris Olah’s work on transparency

- Moritz Hardt’s work on fairness with ML

You can listen to the podcast above and read the full transcript below. You can check out previous podcasts on SoundCloud, iTunes, GooglePlay, and Stitcher.

Ariel: Hi there, I’m Ariel Conn with the Future of Life Institute. As we record and publish this podcast, diplomats from around the world are meeting in Geneva to consider whether to negotiate a ban on lethal autonomous weapons. As a technology that’s designed to kill people, it’s no surprise that countries would consider regulating or banning these weapons, but what about all other aspects of AI? While, most, if not all AI researchers, are designing the technology to improve health, ease strenuous or tedious labor, and generally improve our well-being, most researchers also acknowledge that AI will be transformative, and if we don’t plan ahead, those transformations could be more harmful than helpful.

We’re already seeing instances in which bias and discrimination have been enhanced by AI programs. Social media algorithms are being blamed for impacting elections; it’s unclear how society will deal with the mass unemployment that many fear will be a result of AI developments, and that’s just the tip of the iceberg. These are the problems that we already anticipate and will likely arrive with the relatively narrow AI we have today. But what happens as AI becomes even more advanced? How can people, municipalities, states, and countries prepare for the changes ahead?

Joining us to discuss these questions are Allan Dafoe and Jessica Cussins. Allan is the Director of the Governance of AI program at the Future of Humanity Institute, and his research focuses on the international politics of transformative artificial intelligence. His research seeks to understand the causes of world peace, particularly in the age of advanced artificial intelligence.

Jessica is an AI Policy Specialist with the Future of Life Institute, where she explores AI policy considerations for near and far term. She’s also a Research Fellow with the UC Berkeley Center for Long-term Cybersecurity, where she conducts research on the security and strategy implications of AI and digital governance. Jessica and Allan, thank you so much for joining us today.

Allan: Pleasure.

Jessica: Thank you, Ariel.

Ariel: I want to start with a quote, Allan, that’s on your website and also on a paper that you’re working on that we’ll get to later, where it says, “AI will transform the nature of wealth and power.” And I think that’s sort of at the core of a lot of the issues that we’re concerned about in terms of what the future will look like and how we need to think about what impact AI will have on us and how we deal with that. And more specifically, how governments need to deal with it, how corporations need to deal with it. So, I was hoping you could talk a little bit about the quote first and just sort of how it’s influencing your own research.

Allan: I would be happy to. So, we can think of this as a proposition that may or may not be true, and I think we could easily spend the entire time talking about the reasons why we might think it’s true and the character of it. One way to motivate it, as I think has been the case for people, is to consider that it’s plausible that artificial intelligence would at some point be human-level in a general sense, and to recognize that that would have profound implications. So, you can start there, as, for example, if you were to read Superintelligence by Nick Bostrom, you sort of start at some point in the future and reflect on how profound this technology would be. But I think you can also motivate this with much more near-term perspective and thinking of AI more in a narrow sense.

So, I will offer three lenses for thinking about AI and then I’m happy to discuss it more. The first lens is that of general purpose technology. Economists and others have looked at AI and seen that it seems to fit the category of general purpose technology, which are classes of technologies that provide a crucial input to many important processes, economic, political, and military, social, and are likely to generate these complementary innovations in other areas. And general purpose technologies are also often used as a concept to explain economic growth, so you have things like the railroad or steam power or electricity or the motor vehicle or the airplane or the computer, which seem to change these processes that are important, again, for the economy or for society or for politics in really profound ways. And I think it’s very plausible that artificial intelligence not only is a general purpose technology, but is perhaps the quintessential general purpose technology.

And so in a way that sounds like a mundane statement. General purpose, it will sort of infuse throughout the economy and political systems, but it’s also quite profound because when you think about it, it’s like saying it’s this core innovation that generates a technological revolution. So, we could say a lot about that, and maybe I should just to sort of give a bit more color, I think Kevin Kelly has a nice quote where he says, “Everything that we formally electrified, we will now cognitize. There’s almost nothing we can think of that cannot be made new, different, or interesting by infusing it with some extra IQ.” We could say a lot more about general purpose technologies and why they’re so transformative to wealth and power, but I’ll move on to the other two lenses.

The second lens is to think about AI as an information and communication technology. You might think this is a subset of general purpose technologies. So, other technologies in that reference class would include the printing press, the internet, and the telegraph. And these are important because they change, again, sort of all of society and the economy. They make possible new forms of military, new forms of political order, new forms of business enterprise, and so forth. So we could say more about that, and those have important properties related to inequality and some other characteristics that we care about.

But I’ll just move on to the third lens, which is that of intelligence. So, unlike every other general purpose technology, which applied to energy, production, or communication or transportation, AI is a new kind of general purpose technology. It changes the nature of our cognitive processes, it enhances them, it makes them more autonomous, generates new cognitive capabilities. And I think it’s that lens that makes it seem especially transformative. In part because the key role that humans play in the economy is increasingly as cognitive agents, so we are now building powerful complements to us, but also substitutes to us, and so that gives rise to the concerns about labor displacement and so forth. But also innovations in intelligence are hard things to forecast how they will work and what those implications will be for everything, and so that makes it especially hard to sort of see what’s through the mist of the future and what it will bring.

I think there’s a lot of interesting insights that come from those three lenses, but that gives you a sense of why AI could be so transformative.

Ariel: That’s a really nice introduction to what we want to talk about, which is, I guess, okay so then what? If we have this transformative technology that’s already in progress, how does society prepare for that? I’ve brought you both on because you deal with looking at the prospect of AI governance and AI policy, and so first, let’s just look at some definitions, and that is, what is the difference between AI governance and AI policy?

Jessica: So, I think that there are no firm boundaries between these terms. There’s certainly a lot of overlap. AI policy tends to be a little bit more operational, a little bit more finite. We can think of direct government intervention more for the sake of public service. I think governance tends to be a slightly broader term, can relate to industry norms and principles, for example, as well as government-led initiatives or regulations. So, it could be really useful as a kind of multi-stakeholder lens in bringing different groups to the table, but I don’t think there’s firm boundaries between these. I think there’s a lot of interesting work happening under the framework of both, and depending on what the audience is and the goals of the conversation, it’s useful to think about both issues together.

Allan: Yeah, and to that I might just add that governance has a slightly broader meaning, so whereas policy often sort of connotes policies that companies or governments develop intentionally and deploy, governance refers to those, but also sort of unintended policies or institutions or norms and just latent processes that shape how the phenomenon develops. So how AI develops and how it’s deployed, so everything from public opinion to the norms we set up around artificial intelligence and sort of emergent policies or regulatory environments. All of that you can group within governance.

Ariel: One more term that I want to throw in here is the word regulation, because a lot of times, as soon as you start talking about governance or policy, people start to worry that we’re going to be regulating the technology. So, can you talk a little bit about how that’s not necessarily the case? Or maybe it is the case.

Jessica: Yeah, I think what we’re seeing now is a lot of work around norm creation and principles of what ethical and safe development of AI might look like, and that’s a really important step. I don’t think we should be scared of regulation. We’re starting to see examples of policies come into place. A big important example is the GDPR that we saw in Europe that regulates how data can be accessed and used and controlled. We’re seeing increasing examples of these kinds of regulations.

Allan: Another perspective on these terms is that in a way, regulation is a subset, a very small subset, of what governance consists of. So regulation might be especially deliberate attempts by government to shape market behavior or other kinds of behavior, and clearly regulation is sometimes not only needed, but essential for safety and to avoid market failure and to generate growth and other sorts of benefits. But regulation can be very problematic, as you sort of alluded to, for a number of reasons. In general, with technology — and technology’s a really messy phenomenon — it’s often hard to forecast what the next generation of technology will look like, and it’s even harder to forecast what the implications will be for different industries, for society, for political structures.

And so because of that, designing regulation can often fail. It can be misapplied to sort of an older understanding of the technology. Often, the formation of regulation may not be done with a really state-of-the-art understanding of what the technology consists of, and then because technology, and AI in particular, is often moving so quickly, there’s a risk that regulation is sort of out of date by the time it comes into play. So, there are real risks of regulation, and I think a lot of policymakers are aware of that, but also markets do fail and there are really profound impacts of new technologies not only on consumer safety, but in fairness and other ethical concerns, but also more profound impacts, as I’m sure we’ll get to, like the possibility that AI will increase inequality within countries, between people, between countries, between companies. It could generate oligopolistic or monopolistic market structures. So there are these really big challenges emerging from how AI is changing the market and how society should respond, and regulation is an important tool there, but it needs to be done carefully.

Ariel: So, you’ve just brought up quite a few things that I actually do want to ask about. I think the first one that I want to go to is this idea that AI technology is developing a lot faster than the pace of government, basically. How do we deal with that? How do you deal with the fact that something that is so transformative is moving faster than a bureaucracy can handle it?

Allan: This is a very hard question. We can introduce a concept from economics, which is useful, and that is of an externality. So, an externality is some process that when two market actors transact, I buy a product from a seller, it impacts on a third party, so maybe we produce pollution or I produce noise or I deplete some resource or something like that. And policy often should focus on externalities. Those are the sources of market failure. Negative externalities are the ones like pollution that you want to tax or restrict or address, and then positive externalities like innovation are ones you want to promote, you want to subsidize and encourage. And so one way to think about how policy should respond to AI is to look at the character of the externalities.

If the externalities are local and if the sort of relevant stakeholder community is local, then I think a good general policy is to allow a local authority to develop to the lowest level that you can, so you want municipalities or even smaller groups to implement different regulatory environments. The purpose for that is not only so that the regulatory environment is adapted to the local preferences, but also you generate experimentation. So maybe one community uses AI in one way and another employs it in another way, and then over time, we’ll start seeing which approaches work better than others. So, as long as the externalities are local, then that’s, I think, what we should do.

However, many of these externalities are at least national, but most of them actually seem to be international. Then it becomes much more difficult. So, if the externalities are at the country level, then you need country level policy to optimally address them, and then if they’re transnational, international, then you need to negotiate with your neighbors to converge on a policy, and that’s when you get into much greater difficulty because you have to agree across countries and jurisdictions, but also the stakes are so much greater if you get the policy wrong, and you can’t learn from the sort of trial and error of the process of local regulatory experimentation.

Jessica: I just want to push back a little bit on this idea. I mean, if we take regulation out of it for a second and think about the speed at which AI research is happening and kind of policy development, the people that are conducting AI research, it’s a human endeavor, so there are people making decisions, there are institutions that are involved that rely upon existing power structures, and so this is already kind of embedded in policy, and there are political and ethical decisions just in the way that we’re choosing to design and build this technology from the get-go. So all of that’s to say that thinking about policy and ethics as part of that design process I think is really useful and just to not have them as always opposing factors.

One of the things that can really help in this is just improving those communication channels between technologists and policymakers so there isn’t such a wide gulf between these worlds and these conversations that are happening and also bringing in social scientists and others to join in on those conversations.

Allan: I agree.

Ariel: I want to take some of these ideas and look at where we are now. Jessica, you put together a policy resource that covers a lot of efforts being made internationally looking at different countries, within countries, and then also international efforts, where countries are working together to try to figure out how to address some of these AI issues that will especially be cropping up in the very near term. I was wondering if you could talk a little bit about what the current state of AI policy is today.

Jessica: Sure. So this is available publicly. This is futureoflife.org/ai-policy. It’s also available on the Future of Life homepage. And the idea here is that this is a living resource document, so this is being updated regularly and it’s mapping AI policy developments as they’re happening around the world, so it’s more of an empirical exercise in that way, kind of seeing how different groups and institutions, as well as nations, are framing and addressing these challenges. So, in most cases, we don’t have concrete policies on the ground yet, but we do have strategies, we have frameworks for addressing these challenges, and so we’re mapping what’s happening in that space and hoping that it encourages transparency and also collaboration between actors, which we think is important.

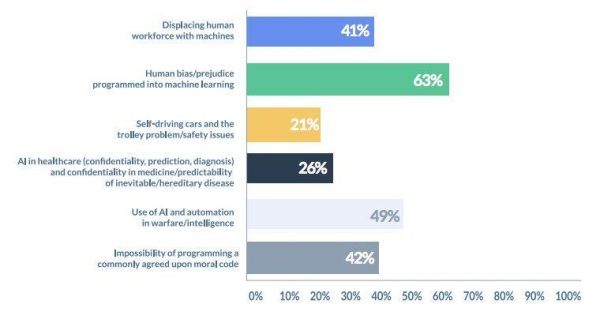

There are three complementary resources that are part of this resource. The first one is a map of national and international strategies, and that includes 27 countries and 6 international initiatives. The second resource is a compilation of AI policy challenges, and this is broken down into 14 different issues, so this ranges from economic impacts and technological unemployment to issues like surveillance and privacy or political manipulation and computational propaganda, and if you click on each of these different challenges, it actually links you with relevant policy principles and recommendations. So, the idea is if you’re a policymaker or you’re interested in this, you actually have some guidance. What are people in the field thinking about ways to address these challenges?

And then the third resource there is a set of reading lists. There are dozens of papers, reports, and articles that are relevant to AI policy debates. We have seven different categories here that include things like AI policy overviews or papers that delve into the security and existential risks of AI. So, this is a good starting place if you’re thinking about how to get involved in AI policy discussions.

Ariel: Can you talk a little bit about some of maybe the more interesting programs that you’ve seen developing so far?

Jessica: So, I mean the U.S. is really interesting right now. There’s been some recent developments. The 2019 National Defense Authorization Act was just signed last week by President Trump, and so this actually made official a new national security commission on artificial intelligence. So we’re seeing the kind of beginnings of a national strategy for AI within the U.S. through these kinds of developments that don’t really resemble what’s happening in other countries. This is part of the defense department, much more tailored to national defense and national security, so there’s going to be 15 commission members looking at a range of different issues, but particularly with how they relate to national defense.

We also have a new joint AI center in the DoD that will be looking at an ethical framework but for defense technologies using AI, so if you compare this kind of focus to what we’ve seen in France, for example, they have a national strategy for AI. It’s called AI for Humanity, and there’s a lengthy report that goes into numerous different kinds of issues; they’re talking about ecology and sustainability, about transparency, much more of a focus on having state-led developments kind of pushing back against the idea that we can just leave this to the private sector to figure out, which is really where the U.S. is going in terms of the consumer uses of AI. Trump’s priorities are to remove regulatory barriers as it relates to AI technology, so France is markedly different and they want to push back against the company control of data and the uses of these technologies. So, that’s kind of an interesting difference we’re seeing.

Allan: I would like to add that I think Jessica’s overview of global AI policy looks like a really useful resource. There’s a lot of links to most of the key, I think, readings that I would think you’d want to direct someone to, so I really recommend people check that out. And then specifically, I just want to respond to this remark Jessica made about sort of U.S. approach letting companies more have a free reign at developing AI versus the French approach, especially well articulated by Macron in his Wired interview is the insight that you’re unlikely to be able to develop AI successfully if you don’t have the trust of important stakeholders, and that mostly means the citizens of your country.

And I think Facebook has realized that and is working really hard to regain the trust from citizens and users, and just in general I think, yeah, if AI products are being deployed in an ecosystem where people don’t trust them, that’s going to handicap the deployment of those AI services. There’ll be sort of barriers to their use, there will be opposition regulation that will not necessarily be the most efficient way of generating AI that’s fair or safe or respects privacy. So, I think this conversation between different governmental authorities and the public and NGOs and researchers and companies around what is good AI, what are the norms that we should expect from AI, and then how do we communicate that and enter into a conversation that, between the public and the developers of AI, is really important and is sort of against U.S. national interests to not have that conversation and not develop that trust.

Ariel: I’d actually like to stick with this subject for a minute because trust is something that I find rather fascinating, actually. How big a risk is it, do you think, that the public could decide, “We just don’t trust this technology and we want it to stop,” and if they did decide that, do you think it would actually stop? Or do you think there’s enough government and financial incentive to continue promoting AI that the public trust may not be as big a deal as it has been for some other technologies?

Jessica: I certainly don’t think that there’s gonna be a complete stop from the companies that are developing this technology, but certainly responses from the public and from their employees can shift behavior. At Google, we’re seeing at Amazon that protests from the employees can lead to changes. So in the case of Google, the employees were upset about the involvement with the U.S. military on Project Maven and didn’t want their technology to be used in that kind of weaponized way, and that led Google to publish their own AI ethics principles, which included specifically that they would not renew that contract and that they would not pursue autonomous weapons. There is certainly a back and forth that happens between the public, between employees of companies and where the technology is going. I think we should feel empowered to be part of that conversation.

Allan: Yeah, I would just second that. Investments in AI and in research and development will not stop, certainly globally, but there’s still a lot of interest that could be substantially harmed, including the public interest from the development of valuable AI services and growth from a breakdown in trust. AI services really depend on trust. You see this with the big AI companies that rely on having a large user base and generating a lot of data. So the algorithms often depend on lots of user interaction and having a large user base to do well, and that only works if users are willing to share their data, if they trust that their data is protected and being used appropriately, if there are not political movements to inefficiently, or not in the interest of the public, prevent the accumulation and use of data.

So, that’s one of the big areas, but I think there are a lot of other ways in which a breakdown in trust would harm the development of AI. It will make it harder for start ups to get going. Also, as Jessica mentioned, I think AI researchers are, they’re not just in it for the money. A lot of them have real political convictions, and if they don’t feel like their work is doing good or if they have ethical concerns with how their work is being used, they are likely to switch companies or express their concerns internally as we saw at Google. I think this is really crucial for a country from the national interest perspective. If you want to have a healthy AI ecosystem, you need to develop a regulatory environment that works but also have relationships with key companies and the public that are informed and sort of stays within the bounds of the public interest in terms of all of the range of ethical and other concerns they would have.

Jessica: Two quick additional points on this issue of trust. The first is that policymakers should not assume that the public will necessarily trust their reaction and their approach to dealing with this, and there’s differences in the public policy processes that happen that can enable greater trust. So, for example, I think there’s a lot to learn from the way that France went about developing their strategy. It took place over the course of a year with hundreds of interviews, extremely consultative with members of the public, and that really encourages buy-in from a range of stakeholders, which I think is important. If we’re gonna be establishing policies that stick around, to have that buy-in not only from industry but also from the publics that are implicated and impacted by these technologies.

A second point is just the importance of norms that we’re seeing in creating cultures of trust, and I don’t want to overstate this, but it’s sort of a first step, and I think we also need monitoring services, we need accountability, we need ways to actually check that these norms aren’t just kind of disappearing into the ether but are upheld in some way. But that being said, they are an important first step, and so I think things like the Asilomar AI principles which were again, a very consultative process that were developed by a large number of people and iterated upon, and only those that had quite a lot of consensus made it into the final principles. We’ve seen thousands of people sign onto those. We’ve seen them being referenced around the world, so those kinds of initiatives are important in kind of helping to establish frameworks of trust.

Ariel: While we’re on this topic, you’ve both been sort of getting into roles of different stakeholders in developing policy and governance, and I’d like to touch on that more explicitly. We have, obviously governments, we have corporations, academia, NGOs, individuals. What are the different roles that these different stakeholders play and do you have tips for how these different stakeholders can try to help implement better and more useful policy?

Allan: Maybe I’ll start and then turn it over to Jessica for the comprehensive answer. I think there’s lots of things that can be said here, and really most actors should be involved in multiple ways. The one I want to highlight is I think the leading AI companies are in a good position to be leaders in shaping norms and best practice and technical understanding and recommendations for policies and regulation. We’re actually quite fortunate that many of them are doing an excellent job with this, so I’ll just call out one that I think is commendable in the extent to which it’s being a good corporate citizen and that’s Alphabet. I think they’ve developed their self-driving car technology in the right way, which is to say, carefully. Their policies towards patents is, I think, more in the public interest and that is that they oppose offensive patent litigation and have really sort of invested in opposing that. You can also tell a business case story for why they would do that. I think they’ve supported really valuable AI research that otherwise groups like FLI or other sort of public interest funding sources would want to support. To example, I’ll offer Chris Olah, in Google Brain, who has done work on transparency and legibility of neural networks. This is highly technical but also extremely important for safety in the near and long-term. This is the kind of thing that we’ll need to figure out to have confidence that really advanced AI is safe and working in our interest, but also in the near-term for understanding things like, “Is this algorithm fair or what was it doing and can we audit it?”

And then one other researcher I would flag, also at Google Brain, is Moritz Hardt has done some excellent work on fairness. And so here you have Alphabet supporting AI researchers who are doing, really I think, frontier work on the ethics of AI and developing technical solutions. And then of course, Alphabet’s been very good with user data and in particular, DeepMind, I think, has been a real leader in safety, ethics, and AI for good. So I think the reason I’m saying this is because I think we should develop a norm, a strong norm that says, “Companies who are the leading beneficiaries of AI services in terms of profit have a social responsibility to exemplify best practice,” and we should call out the ones who are doing a good job and also the ones that are doing bad jobs and encourage the ones that are not doing good jobs to do better, first through norms and then later through other instruments.

Jessica: I absolutely agree with that. I think that we are seeing a lot of leadership from companies and small groups, as well, not even just the major players. Just a couple days ago, an AI marketing company released an AI ethics policy and just said, “Actually, we think every AI company should do this, and we’re gonna start and say that we won’t use negative emotions to exploit people, for example, and that we’re gonna take action to avoid prejudice and bias.” I think these are really important ways to establish as best practices exactly as you said.

The only other thing I would say is that more than other technologies in the past, AI is really being led by a small handful of companies at the moment in terms of the major advances. So I think that we will need some external checks on some of the processes that are happening. If we kind of analyze the topics that come up, for example, in the AI ethics principles coming from companies, not every issue is being talked about. I think there certainly is an important role for governments and academia and NGOs to get involved and point out those gaps and help kind of hold them accountable.

Ariel: I want to transition now a little bit to talk about Allan, some of the work that you are doing at the Governance of AI program. You also have a paper that I believe will be live when this podcast goes live. I’d like you to talk a little bit about what you’re doing there and also maybe look at this transition of how we go from governance of this narrow AI that we have today to looking at how we deal with more advanced AI in the future.

Allan: Great. So the Governance of AI Program is a unit within the Future of Humanity Institute at the University of Oxford. The Future of Humanity Institute was founded by Nick Bostrom, and he’s the Director, and he’s also the author of Superintelligence. So you can see a little bit from that why we’re situated there. The Future of Humanity Institute is actually full of really excellent scholars thinking about big issues, as the title would suggest. And many of them converged on AI as an important thing to think through, an important phenomenon to think through, for the highest stakes considerations. Almost no matter what is important to you, over the time scale of say, four decades and certainly further into the future, AI seems like it will be really important for realizing or failing to realize those things that are important to you.

So, we are primarily focused on the highest stakes governance challenges arising from AI, and that’s often what we’re indicating when we talk about transformative AI. Is that we’re really trying to focus on the kinds of AI, the developments in AI, and maybe this is several decades in the future, that will radically transform wealth and power and safety and world order and other values. However, I think you can motivate a lot of this work by looking at near-term AI, so we could talk about a lot of developments in near-term AI and how they suggest the possibilities for really transformative impacts. I’ll talk through a few of those or just mention a few.

One that we’ve touched on a little bit is labor displacement and inequality. This is not science fiction to talk about the impact of automation and AI on inequality. Economists are now treating this as a very serious hypothesis, and I would say the bulk of belief within the economics community is that AI will at least pose displacement challenges to labor, if not more serious challenges in terms of persistent unemployment.

Secondarily is the issue of inequality that there’s a number of features of AI that seem like they could increase inequality. The main one that I’ll talk about is that digital services in general, but AI in particular, have what seems like a natural global monopoly structure. And this is because the provision of an AI service, like a digital service, often has a very low marginal cost. So it’s effectively free for Netflix to give me a movie. In a market like that for Netflix or for Google Search or for Amazon e-commerce, the competition is all in the fixed cost of developing the really good AI “engine” and then whoever develops the best one can then outcompete and sort of capture the whole market. And then the size of the market really depends on if there’s sort of cultural or consumer heterogeneity.

All of this to say, we see these AI giants, the three in China and the handful in the U.S. Europe, for example, is really concerned that they don’t have an AI giant, and they’re wondering how do they produce an AI champion. And it’s plausible that a combination of factors means it’s actually going to be very hard for Europe to generate the next AI champion. So this has important geopolitical implications, economic implications, implications for welfare of citizens in these countries, implications for tax.

Everything I’m saying right now is really, I think, motivated by near-term and quite credible possibilities. We can then look to other possibilities, which seem more like science fiction but are happening today. For example, the possibilities around surveillance and control from AI and from autonomous weapons, I think, are profound. So, if you have a country or any authority, that could be a company as well, that is able to deploy surveillance systems that can be surveilling your online behavior, for example your behavior on Facebook or your behavior at the workplace. When I leave my chair, if there’s a camera in my office, it can watch if I’m working and what I’m doing, and then of course my behavior in public spaces and elsewhere, then the authority can really get a lot of information on the person who’s being surveilled. And that could have profound implications for the power relations between governments and publics or companies and publics.

And this is the fundamental problem of politics, is how do you build this leviathan, this powerful organization that doesn’t abuse its power. And we’ve done pretty well in many countries developing institutions to discipline the leviathan so that it doesn’t abuse its power, but AI is now providing this dramatically more powerful surveillance tool and then sort of coercion tool, and so that could, say, at the least, enable leaders of totalitarian regimes to really reinforce their control over their country. More worryingly, it could lead to sort of an authoritarian sliding in countries that are less robustly democratic, and even countries that are pretty democratic, they might still worry about how it will shift power between different groups. And that’s another issue area, which again is, the stakes are tremendous, but we’re not invoking sort of radical advances in AI to get there.

And there’s actually some more that we could talk about, such as strategic stability, but I’ll skip it. Those are sort of all the challenges from near-term AI — AI as we see it today or likely it’s going to be coming in five years. But AI’s developing quickly, and we really don’t know how far it could go, how quickly. And so it’s important to also think about surprises. Where might we be in 10, 15, 20 years? And this is obviously very difficult, but I think, as you’ve mentioned, because it’s moving so quickly, it’s important that some people, scholars and policymakers, are looking down the tree a little bit farther to try to anticipate what might be coming and what we could do today to steer in a better direction.

So, at the Governance of AI Program, we work on every aspect of the development and deployment and regulation and norms around AI that we see as bearing on the highest stakes issues. And this document that you mentioned, it’s entitled AI Governance: A Research Agenda, is an attempt to articulate the space of issues that people could be working on that we see as potentially touching on these high stakes issues.

Ariel: One area that I don’t think you mentioned that I would like to ask about is the idea of an AI race. Why is that a problem, and what can we do to try to prevent an AI race from happening?

Allan: There’s this phenomenon that we might call the AI race, which has many layers and many actors, and this is the phenomenon where actors (those could be an AI researcher, they could be a lab, they could be a firm, they could be a country or even a region like Europe) perceive that they need to work really hard, invest resources, and move quickly to gain an advantage in AI — in AI capabilities, in AI innovations, deploying AI systems, entering a market — because if they don’t, they will lose out on something important to them. So, that could be, for the researchers, it could be prestige, right? “I won’t get the publication.” For firms it could be both prestige and maybe financial support. It could be a market. You might capture or fail to capture a really important market.

And then for countries, there’s a whole host of motivations. Everything from making sure there’s industries in our country for our workers to having companies that pay tax revenue so that the idea is if we have an AI champion, then we will have more taxable revenue but also other advantages. There’ll be more employment. Maybe we can have a good relationship with that champion and that will help us in other policy domains. And then, of course, there’s the military considerations that if AI becomes an important complement to other military technologies or even crucial tech in itself, then countries are often worried about falling behind and being inferior and always looking towards what might be the next source of advantage. So, that’s another driver for this sense that countries want to not fall behind and get ahead.

Jessica: We’re seeing competing interests at the moment. There are nationalistic kinds of tendencies coming up. We’re seeing national strategies emerging from all over the world, and there’s really strong economic and military motivations for countries to take this kind of stance. We’ve got Russian President Vladimir Putin telling students that whoever leads artificial intelligence will be the ruler of the world. We’ve got China declaring a national policy that they intend to be the global leader in AI by 2030, and other countries as well. Trump has said that he intends for the U.S. to be the global leader. The U.K. has said similar things.

So, there’s a lot of that kind of rhetoric coming from nations at the moment, and they do have economic and military motivations to say that. They’re competing for a relatively small number of AI researchers and a restricted talent pool, and everybody’s searching for that competitive advantage. That being said, as we see AI develop, particularly from more narrow applications to potential more generalized ones, the need for international cooperation, as well as more robust safety and reliability controls, are really going to increase, and so I think there are some emerging signs of international efforts that are really important to look to, and hopefully we’ll see that outweigh some of the competitive race dynamics that we’re seeing now.

Allan: The sort of crux of the problem is if everyone’s driving to achieve this performance achievement, they want to have the next most powerful system, and if there’s any other value that they might care about or society might care about, that’s sort of in the way or that there’s a trade-off. They have an incentive to trade away some of that value to gain a performance lead. Things that we see today, like privacy, so maybe countries that have a stricter privacy policy may have troubles generating an AI champion. Some look to China and see that maybe China has an AI advantage because it has such a cohesive national culture and close relationship between government and the private sector, as compared with, say, the United States, where you can see a real conflict at times between, say, Alphabet and parts of the U.S. government, which I think the petition around Project Maven really illustrates.

So, values you might lose include privacy or maybe not developing autonomous weapons, according to some ethical guidelines that you would want. There’s other concerns that put people’s lives at stake, so if you’re rushing to market with a self-driving car that isn’t sufficiently safe, then people can die. And the small numbers, they’re independent risks, but if say the risk that you’re deploying is that the self-driving car system itself is hackable at scale, then you might be generating a new weapon of mass destruction. So, there’s these accident risks or malicious use risks that are pretty serious, and then when you really start looking towards AI systems that would be very intelligent, hard for us to understand because they’re sort of opaque, complex, fast moving when they’re plugged into financial systems, energy grids, cyber systems, cyber defense, there’s an increasing risk that we won’t even know what risks we’re exposing ourselves to because of these highly complex interdependent, fast-moving systems.

And so if we could sort of all take a breath and reflect a little bit, that might be more optimal from everyone’s perspective. But because there’s this perception of a prize to be had, it seems likely that we are going to be moving more quickly than is optimal. It’s a very big challenge. It won’t be easily solved, but in my view, it is the most important issue for us to be thinking about and working towards over the coming decades, and if we solve it, I think we’re much more likely to develop beneficial advanced AI, which will help us solve all our other problems. So I really see this as the global issue of our era to work on.

Ariel: We sort of got into this a little bit earlier, but what are some of the other countries that have policies that you think maybe more countries should be implementing? And maybe more specifically, if you could speak about some of the international efforts that have been going on.

Jessica: Yeah, so an interesting thing we’re seeing from the U.K. is that they’ve established a center for data ethics and innovation, and they’re really making an effort to prioritize ethical considerations of AI. So I think it remains to be seen exactly what that looks like, but that’s an important element to keep in mind. Another interesting thing to watch, Estonia is working on an AI law at the moment, so they’re trying to make very clear guidelines so that when companies come in and they want to work on AI technology in that country, they know exactly what the framework they’re working in will be like, and they actually see that as something that can help encourage innovations. I think that’ll be a really important one to watch, as well.

But there’s a lot of great work happening. There’s task forces emerging, and not just at the federal level, at the local level, too. New York now has an algorithm monitoring task force and actually trying to see where are algorithms being used in public services and trying to encourage accountability about where those exist, so that’s a really important thing that potentially could spread to other states or other countries.

And then you mentioned international developments, as well. So, there are important things happening here. The E.U. is certainly a great example of this right now. 25 European countries signed a Declaration of Cooperation on AI. This is a plan, a strategy to actually work together to improve research and work collectively on the kind of social and security and legal issues that come up around AI. There’s also, at the G7 meeting, they signed, it’s called the Charlevoix Common Vision for the Future of AI. That again, it’s not regulatory, but setting out a vision that includes things like promoting human-centric AI and fostering public trust, supporting lifelong learning and training, as well as supporting women and underrepresented populations in AI development. So, those kinds of things, I think, are really encouraging.

Ariel: Excellent. And was there anything else that you think is important to add that we didn’t get a chance to discuss today?

Jessica: Just a couple things. There are important ways that government can shape the trajectory of AI that aren’t just about regulation. For example, deciding how to leverage government investment really changes the trajectory of what AI is developed, what kinds of systems people prioritize. That’s a really important policy lever that is different from regulation that we should keep in mind. Another one is around procurement standards. So, when governments want to bring AI technologies into government services, what are they going to be looking for? What are the best practices that they require for that? So, those are important levers.

Another issue just is somewhat taken for granted in this conversation but just to state it, is that, shaping AI for a safe and beneficial future is, we can’t just have technical fixes; these are really built by people, and we’re making choices about how and where they’re deployed and for what purposes, so these are social and political choices. This has to be a multidisciplinary process, and involve governments along with industry and civil society, so really encouraging to see these kinds of conversations take place.

Ariel: Awesome. I think that’s a really nice note to end on. Well, so Jessica and Allan, thank you so much for joining us today.

Allan: Thank you, Ariel, it was a real pleasure. And Jessica, it was a pleasure to chat with you. And thank you to all the good work coming out of FLI promoting beneficial AI.

Jessica: Yeah, thank you so much, Ariel, and thank you Allan, it’s really an honor to be part of this conversation.

Allan: Likewise.Ariel: If you’ve been enjoying the podcasts, please take a moment to like them, share them, follow us on whatever platform you’re listening to us on. And, I will be back again next month, with a new pair of experts.