Aliens in Orbit? Probably Not. $100K on a Kickstarter to Check? Oh, Sure

YESTERDAY, ASTRONOMER TABETHA Boyajian revealed the first data from her telescope survey of a very special star. For almost four months, she’s been using the Las Cumbres Observatory Global Telescope Network to watch for the unpredictable dimmings of KIC 8462852, a star 1,480 light years away. Its strange flickering pattern could have many explanations—stars, asteroids, or comets passing between there and Earth. But the one that turned this star into a star—making Boyajian’s new survey possible—is aliens.

This new research wouldn’t exist if not for the support of 1,762 people who signed on to Boyajian’s Kickstarter campaign—to whom she emailed a sneak data-peek yesterday. And there’s an entire subreddit devoted to discussion of what people have come to call “Tabby’s Star.” “Together we’ll get to the bottom of the greatest mystery we’ve perhaps ever faced as a scientific community,” posted a user named Pringlecks, after another member shared Boyajian’s email to the forum. Tabby’s Star has a logo, a moniker, a figurehead, a cohesive online presence, and a fan base. It’s kind of a brand now—and it points to a new way of doing science.

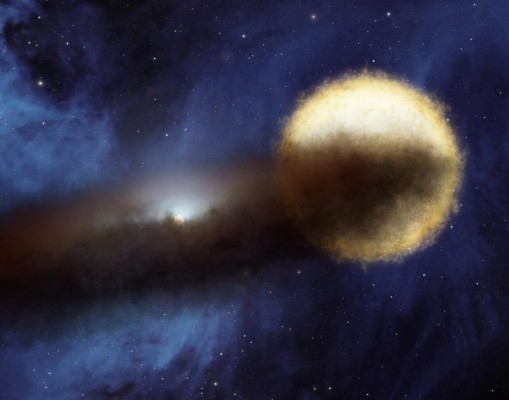

Tabby’s Star began its celebrity ascent more than five years ago, when the Kepler exoplanet telescope collected some weird data. In March 2011, scientists believe something huge passed in front of KIC 8462852—whatever it was had to be big enough to block 15 percent of its light. On February 28, 2013, it happened again, this time blocking 22 percent (for reference, a Jupiter transit darkens the Sun by just 1 percent.). The data also showed a bunch of smaller, irregular dips in brightness.

A group of citizen scientists called the Planet Hunters were the first to notice. When they saw KIC 8462852’s weird behavior in the Kepler data, they alerted Boyajian, a member of the Planet Hunters science team. She wasn’t sure what she was looking at. But she soon brainstormed astronomical explanations detailed in the discovery paper—subtitle: “Where’s the Flux?” (WTF).

She didn’t include another idea that astronomer Jason Wright first proposed to her: What if “alien megastructures,” big construction projects, circled the star?

Boyajian eventually embraced the megastructures as a (last-resort) hypothesis. But she also realized she could harness (and monetize) excitement in maybe-possibly-aliens to work on solving the mystery of KIC 8462852. Because the star’s dips don’t seem to come at regular intervals, she needed a long-term, every-day espionage program to be sure they catch the action. The Kickstarter page for the Most Mysterious Star in the Universe was born in May 2016.

Its $100,000 ask would allow Boyajian’s team to monitor the star for one year using the private Las Cumbres telescope network. “It was a long shot,” says Boyajian. “I’m a regular scientist. I don’t have the regular outlets to blast the notice that we’re doing this out to millions of people.”

But it worked. In 30 days, 1,762 backers donated more than $107,000. “We are overwhelmed and humbled to see the amount of public support for WTF science!” Boyajian wrote.

An Uneasy Partnership

Although Boyajian was cautious about using the word “megastructures” on the Kickstarter page, she says that is, of course, what most of the backers are cheering for. Astronomers are often wary of associating themselves with an alien hypothesis, lest they be lumped with UFO spotters or accused of hyping that unlikeliest explanation for publicity. But, the truth is, people get more excited about hypothetical extraterrestrials than they do about swarms of comets (the current leading explanation). Even though comet swarms are also cool.

And maybe that’s okay. The community is psyched for this science, which they can see unfolding—can help unfold. Tabby’s Star is a star of the people: Start to finish, it’s the story of non-professionals interacting with inexplicable data. They uncovered it in the first place; they put it on Boyajian’s radar; their clicks made it popular; and now their disposable income is funding a private project to get more data that they will be able to interact with.

They want more of it. And they’re getting it. Boyajian created an informational website called Where’s The Flux?, and she hopes to hire a student to improve it as part of her new faculty job at Louisiana State University. Tabby’s Star has PR.

The official website isn’t the only place where fans interact—or even the biggest. Tabby’s stardom is so great that its fans want to talk—a lot. “I get a dozen emails a day,” says Boyajian. “I read them all. I really do. But it’s impossible to reply to all of them. And I felt bad about that. So I was like, ‘I would like a place where I can point people to here is people who like to discuss this.’”

Hello, reddit. The official /r/KIC8462852 page has more than 3,000 members. (Those numbers doubled after August 4, when a study showed that the star faded steadily, by about 1 percent total, over the first 1,000 days of the Kepler mission, but then its brightness crashed by 2.5 percent over just the next 200 days.) Some posts are technical (“The Gaia data release and Tabby’s Star: This is a great ELI5 outline of the Parallax info coming out on Sept 14, 2016”), others a little more out there (“Should we be worried about Tabby’s Star?”)

I’m just going to go ahead and answer that for you: No.

The Next Phase

And now the crowd is getting new data. Since the beginning of May, the Las Cumbres follow-up project has been looking at Tabby’s Star every two or so hours in multiple colors. Enthusiasts can check out the public data-processing software code. Citizen observers with backyard telescopes can also contribute their own observations, and view others’, through the American Association of Variable Star Observers.

No one knows for sure when the star will start acting up again, or how long it may take to create, confirm, and deny hypotheses. And one hard thing about public involvement is that science is slow and, day to day, kind of boring. Boyajian and her team will have to manage people’s expectations, in addition to giving them data.

And then when something does happen, what’s the protocol? Contact another telescope right away for follow-up? Alert their community after it’s confirmed? What if it’s a false alarm?

It’s the same problem SETI scientists face, and the reason they do have an official protocol, called the “Declaration of Principles Concerning Activities Following the Detection of Extraterrestrial Intelligence.”

It’s a lot of responsibility, especially for a person who just started a new job and actually spends 90 percent of her time on other research. The fans, including other scientists, await the day Boyajian will announce that her star is acting up again, and the data to back it. But what if—and please don’t kill me for asking this—the team rules out every other hypothesis and finds convincing evidence that, OK, yeah, fine, it’s aliens.

Best to, like the “Declaration of Principles,” confirm the discovery and then disseminate it “promptly, openly, and widely through scientific channels and public media, observing the procedures in this declaration.” By which I am pretty sure the International Academy of Astronautics meant “Post it to Reddit.”