Why are palaeontologists suing Trump?

Research published earlier this year suggested that the only area of science that liberals and conservatives could bond over, was dinosaurs. Everyone loves Brontosaurus, right? Whatever else may be going wrong in the world, surely palaeontology is safe from the ravages of politics?

At the start of December Trump announced plans for the biggest loss of protected public lands in the history of the US. By gutting two of America’s National Monuments – named Grand Staircase-Escalante, and Bears Ears – he will eradicate over two million acres of land from government protection. These areas were designated because they contain thousands of archaeological sites, landscapes sacred to Native American tribes, virtually pristine wilderness, and unique geology.

Among the countless geological treasures, are palaeontological specimens of international importance, spanning 320 million years of life on earth. Much of this will be open to destruction if planned cuts go ahead.

But the scientists are fighting back. Almost as soon as Trump had spoken, the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology (SVP) made an announcement of their own: they are suing the President of the United States.

The Society represents more than 2,300 members internationally, from professionals to students, artists, preparators, and those simply passionate about palaeontology. Around 10% of SVP members have been actively engaged in research at these two monuments.

“Because science is an evidence-based process, it is important that sites remain intact and that the fossils go into the public trust. The monument ensures that the same sites can be revisited in a hundred years when technologies, methods, and questions have changed. Scientists therefore choose to conduct research in protected places like these national monuments whenever they can. Trump’s changes have now exposed many sites to potential destruction.”

A national monument is similar to a national park, but whereas a national park must be established by congress, national monuments can be proclaimed by the President. First created by Theodore Roosevelt under the 1906 Antiquities Act, they were primarily conceived to protect Native American cultural and archaeological sites and artefacts, but also “other objects of historic or scientific interest” – including fossils. Indeed, one of the first national monuments created was the Petrified Forest in Arizona; where Triassic tree ferns, ginkgoes and cycads scatter the landscape.

President Theodore Roosevelt stands with naturalist John Muir on Glacier Point, above Yosemite Valley – now Yosemite National Park – California, USA. Photograph: Bettmann/Bettmann Archive

The national monuments cuts will supposedly put the land back in the hands of the people, rather than “a small handful of very distant bureaucrats”. National monuments, like all protected areas, are actually designated in order to preserve sites of importance for the public, in posterity. The billionaire president seeks support from a small handful of conservative ranch owners – and from the fossil fuel companies who would undoubtedly benefit from access to any coal, oil and gas on these lands.

Fossil fuels may be on many people’s minds since the announcement, but these are far from the most precious fossils to be found in these parks.

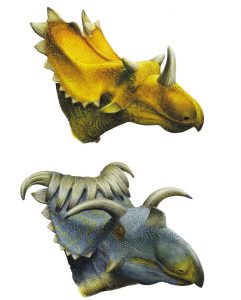

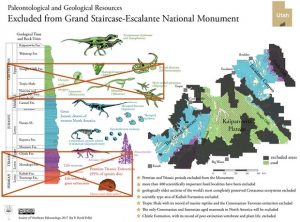

Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument in Utah was established in 1996, and has yielded one of the most diverse herbivorous dinosaur faunas in the world. As many as twenty-five new species of dinosaur have been found in Grand Staircase-Escalante in the last two decades. The stratigraphy spans from the Permian, around 270m years ago, all the way through the Mesozoic ‘time of the dinosaurs’, to the Late Cretaceous. Polly describes it as “almost literally erupting with Late Cretaceous fossils that have forced us to rethink Mesozoic ecosystems and the processes that control biodiversity then and now.”

Fossils from Grand Staircase-Escalante also include the largest Triassic petrified forest outside of Arizona, rare Cretaceous mammals, dinosaur and early mammal footprints, and multiple type sections and localities (the rocks that define a geological unit or area). Many Cretaceous marine fossils would no longer be protected under the new boundaries, including key marine reptiles such as the oldest known mosasaurs, and plesiosaurs, ichthyosaurs and pliosaurs.

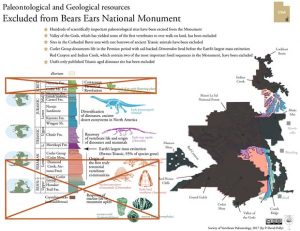

Lying in the heart of Utah’s Canyon Country, Bears Ears National Monument gets its name from the two symmetrical towers of sandstone which dominate the landscape, and have been sacred to Navajo, Hopi, Ute and New Mexico pueblo people for hundreds, if not thousands of years. Scientific papers on fossils from Bears Ears were first published in the 1890s, and since then looting and illegal excavations have seen the loss of many important fossils, hindering preservation and scientific research. Preserving these fossils was part of the rationale for putting this National Monument protection in place last year.

The rocks at Bears Ears reach back even further than at Grand Staircase-Escalante, right into the woodland world of the Carboniferous, 320mya. The Carboniferous is so-named for the coal it bears, formed from these global rainforests, but the rocks at Bears Ears are primarily marine; telling tales from a period when this arid desert was the bottom of a warm ocean. Bears Ears is also unique in preserving ecosystems from the Late Permian, “the first ecosystems that were dominated by vertebrates, in the time of the sail-backed Dimetrodon and its relatives” says Polly. This time period preceded the biggest mass extinction of all time, which cleared a path for the evolution of the iconic Mesozoic reptiles: the dinosaurs, and marine and flying reptiles. The Triassic also holds the origins of our own lineage, the mammals.

Bone beds from the Triassic will be excluded from protection under the proposed cuts to the National Monument, as will Cretaceous rocks that record the earliest flowering plants, called angiosperms, and multiple Quaternary-aged sites – the time between two and fifty-eight million years that includes the formation of modern ecosystems in the North American continent.

I asked Polly what he thought of the President’s claim that he was giving the land back to the public. “The President’s claim is misleading, probably intentionally so. These Monuments already belong to the public, and they exist specially to protect specific resources that belong to the public and are not found elsewhere. One reason the public should care [about the cuts] is that these sites and the history they preserve belong to the public. The fossils collected there remain public property. Everyone has the chance to enjoy them, everyone can learn the stories they tell. If we lose them, they are gone for everyone.” He added, “contrast that to coal – when coal, gas, or petroleum are collected they become private property, they are sold for someone else’s profit, and then they are burned or processed. The public is left with nothing except for a few days of energy – for which they have to pay.”

Although the 3.5m acres that comprise these two parks may seem like a lot of land, it is a drop in the ocean when placed in the context of the vast US landscape. “People talk about how big these monuments are,” says Polly, “but they are collectively only one-half of one percent of US public land, just a speck. The US has 640 million acres of public land. Almost all of that public land is open to ranching, mining, and fossil fuel extraction, as well as other uses, under what is called the ‘multiple-use principle’.” Grand Staircase-Escalante and Bears Ears National Monuments on the other hand, are unique; “[they] have greater restrictions because they have unique resources that would be damaged by ranching, off-road vehicle use, or mining.” He added, “there is more than enough room for ranching and mining without needing to risk the destruction of the special resources found at Grand Staircase and Bears Ears.”

The loss of protected sites for research will naturally also effect jobs, both in the US and abroad. “They will have lost their research permits,” says Polly, “and they may have lost funding streams that help support their work,”

Professor Emily Rayfield, a University of Bristol-based palaeontologist who is current vice-president of SVP, points out that the fossils being found at these national monuments “are not only significant to North American palaeontology, they are of importance to palaeontologists worldwide. For example, both Bears Ears and Grand Staircase-Escalante preserve detailed evidence of how flora and fauna were impacted and subsequently recovered across Earth’s largest ever mass extinction at the end of the Permian 252 million years ago.”

This kind of information isn’t just of interest to a handful of scientists, but informs our understanding of changes taking place today: “we are in dire need of a greater understanding of deep time mass extinction events in order to better understand and mitigate our current biodiversity crisis” Rayfield explains. If Trumps gets his way, none of these key Permian fossils will be protected under the newly proposed monument boundaries.