Coping advice from people with the world’s most stressful jobs

LIFE IS RARELY WORRY-FREE, but unprecedented angst has become a constant. Beyond the regular challenges of everyday existence—chaotic households, traffic jams, overbearing bosses—the looming presence of a deadly virus over the past three years has made even mundane decisions feel fraught.

Any number of things can spark stress, but they all share a common origin. “It’s when the demands on somebody outstrip the resources they have,” says Lynn Bufka, a senior director at the American Psychological Association (APA). The results of that are rarely good. Face a difficult situation, unrealistic expectation, or sudden conflict without the right skills or tools, and you risk melting down or freezing up. That danger increases when you are pressed for time or cannot influence a challenging variable. “The feeling of not having control is anxiety-provoking,” Bufka says. “It’s pretty overwhelming.”

Most people had no experience dealing with the kind of prolonged pressure that came along with the pandemic. But for those with some of the world’s most intense occupations, it’s all just part of the job. Losing their cool is simply not an option. The strategies they employ to keep calm while facing a classroom, saving a life, or defusing a bomb just might help the rest of us deal with whatever’s pushing us to the edge of reason.

The fishing boat captain

THE STRESSORS: In 2021, the people bringing in Dungeness crab, black cod, and other bounties of the earth—the workers in America’s fishing and hunting industries—had the second deadliest job in the United States, coming in just behind loggers, according to the US Bureau of Labor Statistics. “It is extremely hazardous,” says Richard Ogg, captain of the troller Karen Jeanne, which is based in Bodega Bay, California. The gale-force dangers he and his crew face include rough seas, miserable weather, and sleep deprivation. Pulling in a catch big enough to earn the money they need weighs heavily on his mind too. Above all else, though, Ogg feels a sense of guardianship over his team, and finds the biggest challenge can be coping with conflicts that arise among a crew corralled on a 54.5-foot boat miles from shore. That’s no easy feat when dealing with workers who don’t necessarily respect the hazards, the gear, or each other.

THE COPING MECHANISMS: Effective communication is essential to keeping cool. Ogg tends to be egalitarian, even if he as the captain has the final say and will pull rank if he must. He often discusses problems or disagreements with everyone aboard, seeks their perspectives, and considers their viewpoints to zero in on the best solution. He finds that this approach, and accepting that things sometimes go sideways despite his best efforts, helps everyone stay on an even keel whenever things get choppy.

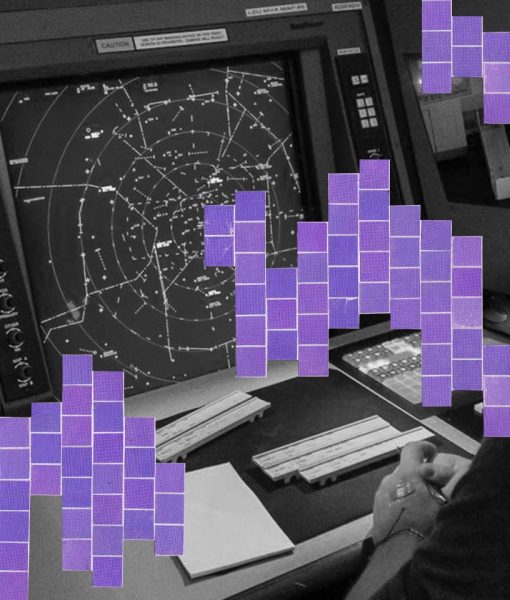

The air traffic controller

THE STRESSORS: Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport hosted nearly 2,000 flights on average every day in 2022, making it the busiest hub in the world last year. “Almost every bit of airspace that we have, there’s going to be planes there,” says air traffic controller Nichole Surunis. Shepherding those thousands of passengers in and out safely requires tremendous concentration and the ability to process information quickly. Variables like bad weather or an unexpected move by a pilot can make an already challenging task even more dynamic at a second’s notice. There’s no time to dwell on what’s at stake. “You have to focus on all these pilots you’re talking to, with all these people on these planes,” Surunis says. In total, there are about 2.9 million travelers who fly into or out of the United States on a given day—and costly delays add to the strain of those minding the traffic. It’s only after the craft are safe that a controller might notice their racing heart and realize just how tense they were.

THE COPING MECHANISMS: Training and experience are key to handling rapidly shifting situations, and Surunis, like all controllers, has lots of both. “You have your Plan A—but you also must have a Plan B and Plan C,” she says. The occupation requires practicing self-care too. Stepping away from her workstation is essential, and mandated: Controllers typically aren’t allowed to go more than two hours without a break. Surunis doesn’t hesitate to tap a union-run support service after an especially grueling day, and she makes a point of unwinding by making time for hobbies like baking. That helps ensure she’s rested and ready to focus on keeping the sky safe.

The trauma surgeon

THE STRESSORS: Doctors who specialize in emergency care rarely have two days that are alike. A routine case like a ruptured appendix can end up on their table as readily as massive trauma. “They can be injured all over their body,” says Daniel Hagler, a critical care surgeon at NewYork-Presbyterian Queens Hospital in New York. “What you do within seconds or minutes of them arriving can be the difference between life and death.” The tension ramps up if he must handle many patients simultaneously. Over time, the strain takes a toll: A study published in The Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery found that nearly one-quarter of doctors in Hagler’s shoes experience symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder.

THE COPING MECHANISMS: Keeping it together requires the ability to triage, focus on what’s important, and put lesser priorities aside. Hagler employs “deliberate and algorithmic thinking”: If you see this, do that. Trust your intuition, using past experience to guide you to the best decision—while accepting that you may be wrong. “Take a step to just ready yourself and settle your nerves, and do what needs to be done,” he says.

The bomb tech

THE STRESSORS: Pipe bombs are the most common homemade explosive devices on American soil, according to the Department of Homeland Security, but the people who specialize in preventing them from blowing up are rare. Techs like Carl Makins, formerly of the Charleston County Sheriff’s Office in South Carolina, often face incendiaries crudely fashioned in someone’s kitchen or basement, so the safest way of deactivating them isn’t always clear. It doesn’t help that the gear includes 85 pounds of hot, uncomfortable Kevlar, making it hard to move. But the biggest source of anxiety is not knowing if someone tampered with the suspicious package or tried to move it in an effort to be helpful before he arrived. “What did you do to it?” Makins often found himself wondering. “Did you make it mad?”

THE COPING MECHANISMS: Makins always tried to compartmentalize his feelings. “You can’t get angry,” he says. “That limits your ability to see everything that you need to see.” He also used humor to help defuse tense situations—pointing out that, say, handling a bomb next to that shiny new pickup might not end well for the truck. He also remained mindful of his limits. If he was too tired, too tense, or just not up to the task, he’d say so and let someone else on the team step in to do the job. “You just tap out,” he says.

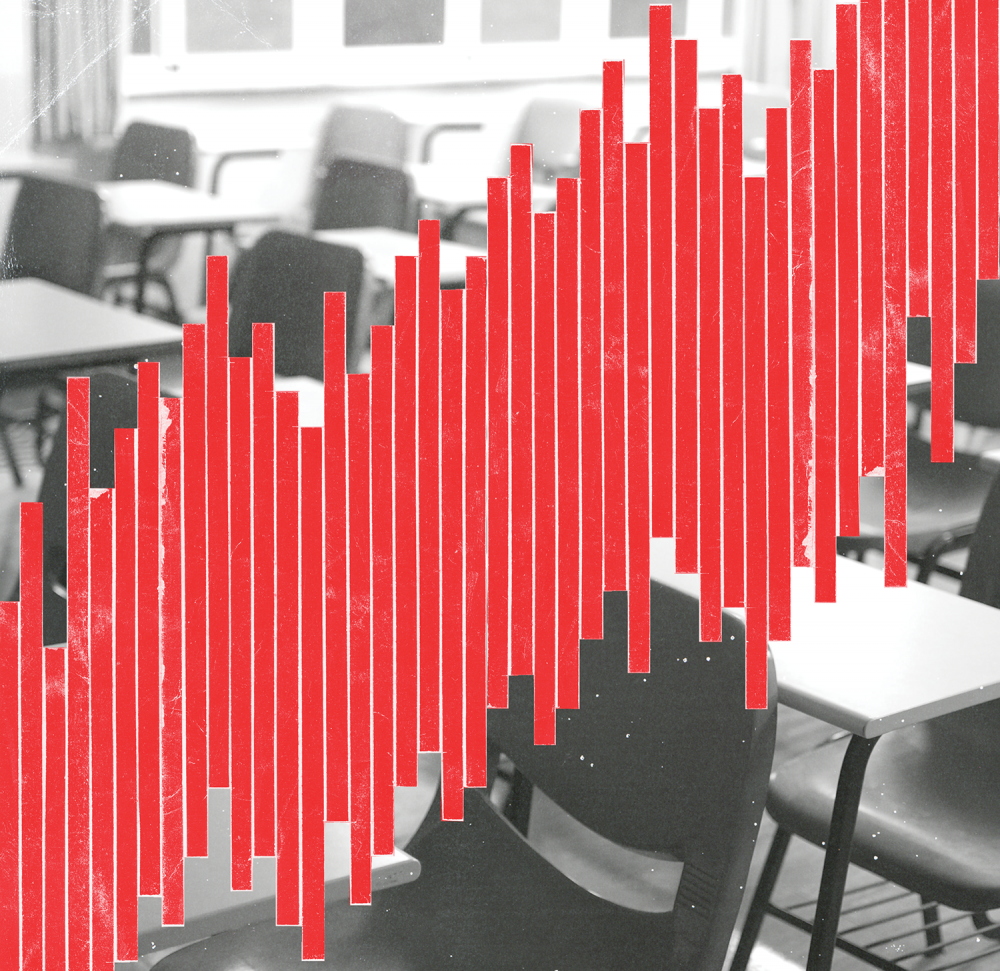

The teacher

THE STRESSORS: Teachers—despite diminishing resources, growing technological distractions, and students who often want to be anywhere but the classroom—are nevertheless saddled with the responsibility of shaping the future. That’s a lot of pressure, which explains why Gallup polls put teaching in a dead heat with nursing for the most stressful profession in the country, and why a RAND Corporation survey shows stress is the number one reason educators quit. And that was before COVID-19 compounded their challenges. When Teresa BlackCloud’s high school students in West Fargo, North Dakota, began taking turns attending class in person and learning from home in the fall of 2020, for example, she had to divide her attention between the pupils in front of her and the “online kids” who might need tech support. “I felt like my brain was split in two,” she says. “If only there were two Miss BlackClouds.” Like many educators, she had to quickly pivot between helping the teens in the classroom and assisting those working remotely.

THE COPING MECHANISMS: Setting clear boundaries is key to handling trying circumstances. BlackCloud had to put the kibosh on responding to pings from kids at all hours because it limited her ability to recharge. “I had to get really good at setting boundaries,” she says. She strives to practice mindfulness and sets aside specific parts of her day for mentally wandering into stressy places. “While I’m brushing my teeth is my time to worry about things,” she says.

The Alaska rescue pilot

THE STRESSORS: Flying a rescue helicopter in Alaska is so intense the Coast Guard requires pilots to complete a tour elsewhere before they can get the gig. The assignment often demands they travel long distances—Air Station Kodiak monitors 4 million square miles of land and sea, an area larger than the entire lower 48 states—in the dark and through extreme conditions. Due to the environs, the Last Frontier has an aviation accident rate more than twice that of the rest of the country. “It is very challenging,” says Lt. Cmdr. Jared Carbajal, who flies MH-60 Jayhawks and often dons night-vision goggles to navigate the inky sky. The haste of operations compounds the tension: Pilots must be airborne within 30 minutes of getting the call to pull someone out of danger. That leaves little time to prepare and sometimes gives Carbajal scant knowledge of what he’ll find when he arrives at the scene. (Carbajal now flies out of US Coast Guard Air Station Sitka, also in Alaska.)

THE COPING MECHANISMS: Managing complex and uncertain scenarios requires focusing only on what you can control. Everything else is a distraction. Carbajal concentrates on one task at a time—calculating flight distance, estimating how much fuel he’ll need, requesting the necessary gear, and so on—that he tackles systematically. He avoids looking too far ahead on his to-do list or fixating on situations he cannot influence, like unusually turbulent waves. “If there’s something that you can’t make a contingency plan for, don’t even waste your time on it,” he says.

An earlier version of this article appeared on popsci.com in January 2021, and this feature first appeared in the Spring 2021 issue. It has been updated since that time.

Read more PopSci+ stories.