Oldest known fossilized reptile skin was dug up in an Oklahoma quarry

Usually, fossilized animal remains result from bits of bone or impressions of a creature long-passed. But sometimes a specific place has just the right conditions to preserve even more. From Richards Spur, a long filled-in cave network and active quarry in southern Oklahoma, a group of paleontologists say they’ve identified and described the oldest fossilized reptile skin ever found. The soft tissue fossil is a rare find–enabled through a series of chance events. It offers a glimpse into a distant evolutionary past that pre-dates both mammals and the oldest dinosaurs.

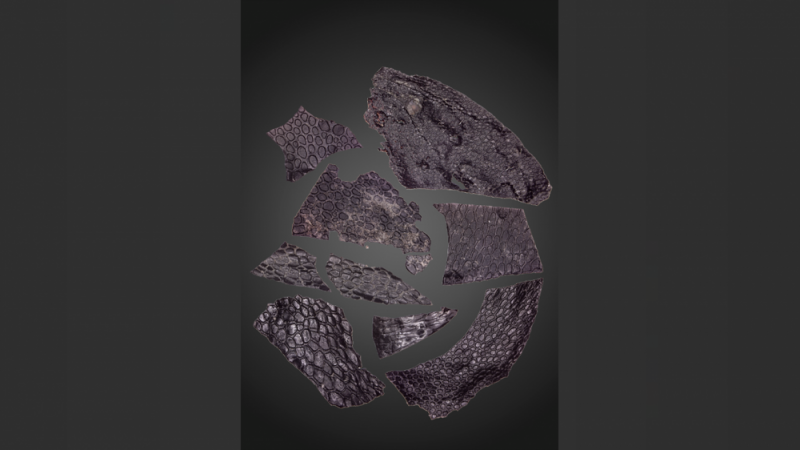

The skin sample, about the size of a fingernail and literally paper thin, is described in a study published on January 10 in the journal Current Biology, along with other fossil findings. The ancient, reptilian skin flake is an estimated 286-289 million years old. That’s at least 21 million years older than the next oldest example and more than 130 million years older than the vast majority of comparable samples, which come from mummified dinosaurs that lived in the late Jurassic, says lead study author Ethan Mooney, a biology master’s student at the University of Toronto studying paleontology.

The fossils’ estimated age is based on the site where they were found. Once, Richards Spur was an open limestone cave, but between 286 and 289 million years ago, it filled in with clay and mud deposits, according to Mooney. During that in-filling process, the cave stopped forming, so the youngest stalagmite rings present in the cave represent the approximate age of the sediments and the fossils they contain, according to previous research using Uranium-Lead radioisotope dating.

Roger Benson, a paleontologist and curator at the American Museum of Natural History who was not involved in the study, agrees these methods and assumptions are sound. “All the evidence, especially what sorts of fossil groups are present, is consistent with an early Permian age (around 300 to 273 million years ago),” he wrote in an email.

In addition to the fossilized piece of “skin proper,” the researchers also documented multiple preserved impressions of skin– a much more common type of fossil to find. But unlike with the impressions, which are essentially the outline of an animal pressed into stone, the researchers were able to assess the cross section of their most notable fossil and identify layers and detail that would’ve otherwise been unknowable.

“At first we thought they were broken pieces of bone,” says Tea Maho, a study co-author and a pHD student at the University of Toronto, of all the epidermal fossils. The skin, she says, “could have just been so easily disregarded until we looked under a microscope.” Then it became clear that they were seeing preserved soft tissue, an exceptionally rare thing among samples that old.

Usually, soft tissue breaks down quickly before it can fossilize. But Richards Spur is a hotbed of paleontological discovery. The study suggests that oxygen-poor sediments and the presence of oil seeps in the cave system helped to preserve the prehistoric animals and carcasses that happened to fall in. In this environment, the skin was mummified–the technical term in paleontology for when organic matter dries out before decaying. Because the site is also an actively mined quarry, new layers of fossils are constantly being uncovered.

“The sheer chance for a soft tissue structure to be preserved, to survive until now–through the mining process–to have been found…and then described by us is quite an incredible story,” Mooney says. Especially given how fragile the preserved epidermis is. “If you were to have pressed it a little too hard, it would have just cracked,” says Maho. Thankfully, for our understanding of vertebrate history, the scientists were careful enough to keep the skin sample from becoming dust.

Though they can’t say for certain what animal the skin specimen was from, Maho and Mooney have an idea. Captorhinus aguti was a lizard-like animal known to have been common in the region during the Permian Period. It had four legs, a tail, was about 10 inches long, and had an omnivorous diet–eating insects, small vertebrates, and occasionally plants. Fossilized skeletal remains of C. aguti have been found at the same site, and aspects of the skin sample are similar to features of those larger fossils.

On top of being the oldest reptile skin ever discovered, Mooney notes the newly described specimen is also the oldest amniote skin ever found. Amniotes are the subcategory of animals that encompasses reptiles, birds, and mammals, and the finding offers insight into a key moment in animal biology. “It comes from a pivotal time in the evolution of life as we know it. It represents the first chapter of higher vertebrate evolution,” from fish and amphibians to creatures not reliant on aquatic habitats to survive or breed. Skin is the body’s largest organ and plays a major role in moisture regulation. Paleontologists have long assumed that good skin was a big deal for early terrestrial animals, now there’s additional fossil evidence for that view, he adds.

Incredibly, the ~289 million-year-old specimen closely resembles present-day crocodile skin, according to the study. Both living crocodiles and the ancient bit of preserved epidermis have a pebble-like texture and a non-overlapping scale pattern. This similarity, Mooney says, is further proof of skin’s outsized role in adapting to life on land. “The fact that we have an example from one of these earliest reptiles and it’s quite consistent with what we see in modern reptiles underscores how important that structure was and how successful it was in doing its job.”

Nearly 300 million years ago, “life would have looked very different,” Mooney says. But reptile skin might not have.