The US government once rented caves in Missouri to store its excess cheese

What’s the weirdest thing you learned this week? Well, whatever it is, we promise you’ll have an even weirder answer if you listen to PopSci’s hit podcast. The Weirdest Thing I Learned This Week hits Apple, Spotify, YouTube, and everywhere else you listen to podcasts every-other Wednesday morning. It’s your new favorite source for the strangest science-adjacent facts, figures, and Wikipedia spirals the editors of Popular Science can muster. If you like the stories in this post, we guarantee you’ll love the show.

Heads up: Rachel and Jess are planning a livestream Q&A in the near future, as well as other fun bonus content! Follow Rachel on Patreon and Jess on Twitch to stay up to date.

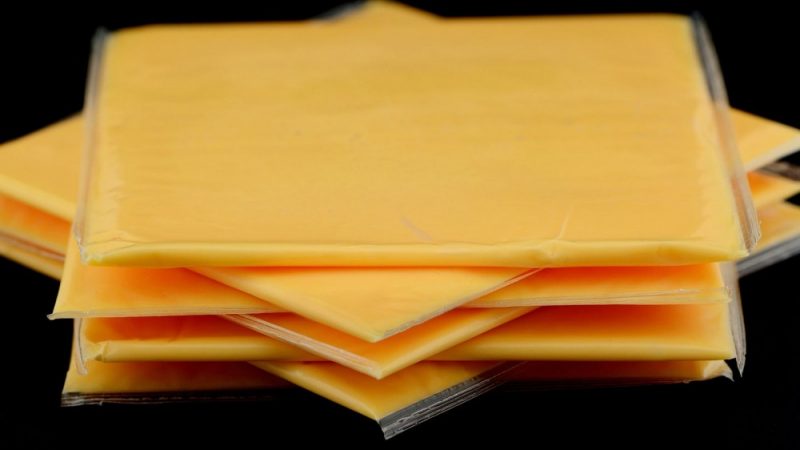

FACT: The United States government once rented caves in Missouri to store its excess cheese purchases.

By Claire Maldarelli

The United States is the most prolific producer of cheese in the world. Seriously: We make three times as much per year as the first runner-up. Around 6.4 million metric tons, to be precise.

But at one point in our nation’s history, we may have taken cheese-making just a little too far. Enter government cheese, and the story of how the United States had to make the tough call to rent out caves as storage space because they bought too much of a good thing.

If you’ve never tried government cheese (I sadly have not), I have been told the product’s taste is a hard thing to forget: a hardy, dense version of the classic “American” cheese found in Kraft singles. In fact, I first stumbled upon the story of government cheese because I was on a hunt for the perfect ingredients for an ideal grilled cheese sandwich. I was hoping there was some cooking trick or cheese combo that I was unaware of. During my search, however, the same surprising opinion cropped up over and over again: Government cheese makes the best grilled cheese sandwich. I had to find out more.

The backstory of government cheese takes us on a journey from a heart-felt effort to help dairy farmers to a food science discovery, and finally, to a cave in the midwest stuffed with cheese. Learn more by listening to this week’s episode of The Weirdest Thing I Learned This Week.

FACT: There are about 120 cockroaches for every person in New York City

By Laura Baisas

This won’t come as a surprise to anyone who has lived in the Big Apple, but roaches pretty much run the city. They started to arrive en masse in NYC in the 1840s, when they were known as “Croton bugs.” This name referred to the newly-constructed Croton aqueduct, which many folks blamed for the sudden infestation. We now know that it wasn’t the aqueduct or its construction itself that made New York such a hospitable place for roaches, but the pipes that so many people suddenly had in their homes to access running water.

By the way, cockroach names often have little to do with their actual places of origin. The so-called Croton bug, for instance, is known more officially as the German cockroach (Blattella germanica)—but the latest research suggests that it came from somewhere in Southeast Asia, possibly by way of Africa. It almost certainly arrived on colonizer ships carrying enslaved peoples and exported goods. There’s actually a long history of cockroaches being named based on prejudice all over the world.

While their origins may be difficult to pinpoint precisely, we know that cockroaches are absolutely thriving here in the United States. Females can have 150 babies each in the course of a lifetime, which lasts only three months or so. They are masters of survival and evolution, and some species have even changed their mating habits to adapt to human pesticide use. When you consider just how much food there is for them in the Big Apple—and the fact that they can fit into cracks that are only about 1/10th of an inch wide—their city-wide dominance starts to make a lot of sense. They’ve done so well that they even have distinct neighborhood lineages.

You can learn more about roaches by listening to this week’s episode. They’re also featured in the new Netflix documentary series “A Real Bug’s Life,” which you can learn more about here.

FACT: Long COVID might leave muscles literally starving for energy

By Rachel Feltman

As many listeners have probably heard before, I have myalgic encephalomyelitis (AKA chronic fatigue syndrome or ME/CFS for short) likely in large part due to that time I got COVID three times in five months back in 2022. (0/10, do not recommend.)

ME/CFS in itself isn’t actually new. The World Health Organization first recognized something like it in 1969. And more importantly, there’s even a Golden Girls episode about it. But it’s been largely misunderstood and ignored for most of that time.

In 1970, two British psychiatrists looked at case notes from 15 outbreaks of ME and concluded that it was caused by mass hysteria. They based this conclusion on the fact that many of the patients had had normal physical test results—and that the illness was more common in women. While other researchers immediately disagreed with them, their work and the lack of clear cause for the disease meant that a lot of doctors were comfortable shrugging it off as totally psychosomatic. The media even started calling it the “yuppie flu,” suggesting it was some kind of burnout only experienced by privileged people.

Fast forward to today, and doctors are seeing a lot of overlap and intersection between ME/CFS and Long COVID, which is an umbrella term for symptoms that persist long after an initial infection with COVID-19. About half of people diagnosed with Long COVID have symptom profiles that also fit ME/CFS. The one upside to this is that it means there’s been a new surge in research on chronic fatigue as an actual, physical condition.

One recent study in particular has patients and clinicians really excited, because it shows physical evidence of—and a possible mechanism for—one of the most common and debilitating symptoms of ME/CFS.

“Post-exertional malaise” is the phenomenon of worsening symptoms some 24-48 hours after physical exertion. I can say from experience that those symptoms aren’t limited to fatigue or muscle pain; I’ve had PEM flare ups that include gastrointestinal symptoms, migraines, severe brain fog and more.

According to a new study, the muscle fibers of ME/CFS patients may literally be starved for energy after physical activity.

Researchers in The Netherlands took muscle biopsies and blood samples from two sets of subjects: 25 of them had long COVID that they’d developed after mild cases of the virus, and had been relatively healthy before that happened. The control group were people who had recovered fully from bouts of COVID-19 and had no lingering symptoms.

The subjects worked out on exercise bikes for about 15 minutes, starting slowly and gradually increasing their intensity. The researchers took blood and muscle samples one week before the test and one day after. People with Long COVID had less muscle strength and lower oxygen uptake, even when they put in the same amount of effort—and had similar heart and lung function. There were also signs that their mitochondria were compromised. Mitochondria provide cellular energy, so if they’re not working properly, tissues can’t get the juice they need to function. Long COVID patients also had more severe muscle damage after their workouts, and had signs of abnormal immune system activity in their muscle fibers.

While this study doesn’t go as far as suggesting a treatment for chronic fatigue, it gives researchers important clues to look into. It’s also an important reminder for patients to listen to their bodies, as conditions like Long COVID can get worse with exertion—even if it’s supposedly mild.