The Xbox One X Is (Not) ‘Liquid Cooled’

There seems to be a bit of confusion about the new vapor chamber cooler used in the Xbox One X. The internet is abuzz with talk of the “liquid cooled” Xbox One X, and this is due in part to the marketing speak used by Microsoft on stage during the Xbox E3 briefing. Although the term “liquid cooled” may be technically accurate, that terminology can be confusing at best, and extremely misleading at worst. Allow us to explain.

The Xbox One X is not liquid cooled in a traditional sense. When you think of something as being “liquid cooled,” the average person pictures an all-in-one cooler or an enthusiast water cooling loop with a water block, radiator, and pump. This form of cooling is the preferred method of heat removal for highly overclocked processors and GPUs that generate enormous amounts of heat. That’s not what’s being used in the Xbox One X.

Simply put, there is nothing “new” about vapor chamber coolers at all. The fact is, this type of cooler has been used for more than a decade to cool blade servers and high-end graphics cards and, even though a vapor chamber cooler does contain a small amount of fluid, it is still more of a heatsink than a water cooling system. Today, the most common use of vapor chamber technology is found in the heatpipes of your CPU / GPU heatsink. They are inexpensive, easy to form into various shapes, and provide superior thermal performance compared to traditional solid metal heat spreaders.

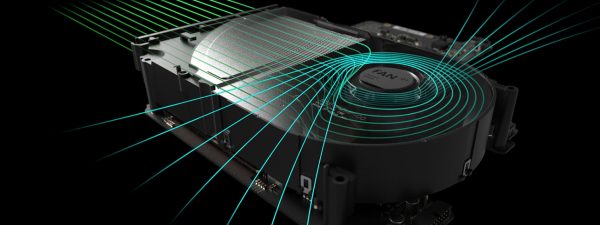

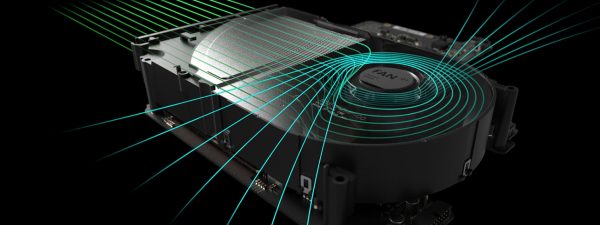

The vapor chamber cooler used in the Xbox One X uses what is known as a two-piece design consisting of upper and lower stamped plates sandwiched together to create a chamber with a sintered wick material on the inner walls. This design allows for complex shapes to be molded into the base plate to enable direct contact with the Xbox One X core and memory chips while heatsink fins are attached to the smooth upper plate.

Coolant, usually in the form of deionised water, is added to the chamber and then vacuum sealed. This causes the wicking material to evenly distribute the fluid throughout the chamber. Once applied to a heat source, the liquid turns to vapor and moves to an area of lower pressure where it dissipate its heat load and returns to liquid form. The cooled liquid then moves back to the heat source by virtue of capillary action and the process repeats itself. As a result, this method of cooling provides evenly spread temperatures across all of its mating surfaces, regardless of the location and density of the heat source.

As you can see, the two methods are quite different, even though they can technically be referred to as “liquid cooling.”

With all that said, the vapor chamber cooler on display at E3 looks robust and, even though we haven’t had a chance to test the new Xbox One X yet, it should definitely handle greater heat loads than a traditional heatsink and fan combinations used in the past.